The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

The Post: The challenge Trump’s tariffs pose for the progressive left

Even in failing, the tariffs could blacken the name of a beloved progressive policy.

Read the original article in the Post

The list of victims of Donald Trump’s incipient trade war grows with every passing second.

Global prosperity, the Chinese economy, American consumers, even the approval ratings of the man himself: all have been hit. Trump’s popularity is tanking, his billionaire backers are revolting (in the active as well as passive sense), and young voters seeking economic stability are fleeing him in droves.

Such chaos understandably elicits schadenfreude among the Donald’s opponents. But this trade war also has the potential to harm the progressive cause – by succeeding, or, to an even greater extent, by failing.

To unfold this apparent paradox, one has to understand the modern American Right, where the political energy has long since shifted away from a purely “neoliberal” – that is, market-led – approach. It embraces instead pro-statist positions that sound weirdly left-wing. State action to protect local manufacturing, and domestic production more generally, is in; untrammelled free trade is out.

What’s driving this shift? Thinking along similar lines to Trump, albeit with slightly more sophistication, American conservatives have clocked the decimation of local communities as steady, high-paying manufacturing jobs have gone offshore, to countries like China with vastly lower labour costs (and, indeed, rampant modern slavery).

Such is their newly rediscovered love of 1950s-style community that some conservatives have even come to embrace trade unions, a key post-WWII force for limiting working hours and – consequently – freeing up time for communal life.

The prospect of more pandemics, and greater armed conflict, has also led conservatives to question whether America should rely so much on foreigners for vital supply chains, and whether – therefore – the nation wouldn’t be more secure making those things at home.

In another world, then, the Trump tariffs, by hammering foreign firms and encouraging manufacturers to shift Stateside, could strengthen both national security and local communities, cementing his appeal among voters abandoned by the left.

But this is not the world that Trump is creating, as economists have been explaining ad nauseam. Because the tariffs change with the president’s passing moods, no sensible foreign firm will invest the billions of dollars needed to relocate production to Pennsylvania or Vermont. No-one builds on shifting sands. Nor would American consumers enjoy the resulting sticker shock: an iPhone built in Chicago might cost twice as much as one built in Shenzhen.

It could, in fact, be the failure of Trump’s trade war that harms the left. Not in an immediate sense: currently the tariffs are a gift to the Democrats. The damage, rather, could be to a recently re-energised intellectual cause among progressives: industrial policy.

In the last decade or so, global thinkers have challenged the 1980s orthodoxy that governments mustn’t attempt to meaningfully shape their economies. Attempting to do so, market fundamentalists have long argued, would simply result in a disastrous attempt to “pick winners”, wasting resources and leaving countries poorer.

But, in an important 2023 paper, “The new economics of industrial policy”, the brilliant Harvard economist Dani Rodrik and his co-authors show just how much the tide has turned on that worldview. The debate about the “East Asian” miracle has been settled, they argue: recent research confirms the view that the astonishing post-WWII acceleration of the Taiwanese, South Korean and other economies was driven by activist governments.

As influential economists like Mariana Mazzucato have argued, well-functioning national governments, with their long time horizons and mandate to pursue the public good, can sometimes see or exploit opportunities that individual firms cannot. Mazzucato has shown, for instance, that the iPhone’s 12 key technologies – lithium-ion batteries, touchscreens, GPS and so on – were all developed or funded by blue-skies public-sector researchers.

National “missions” – America’s drive to put a man on the moon, or Germany’s 1990s push for renewable energy – can also mobilise public and private investment behind new technologies, driving innovation and job growth.

As Rodrik’s paper points out, innovation often depends on clustering – cutting-edge firms locating themselves close to each other – which governments can encourage in various ways. Economies can also get caught in a situation where, for instance, a potential exporting opportunity requires a particular piece of local infrastructure, but no firm will provide either element without the certainty that the other will also be provided.

Governments, Rodrik and co argue, can step in to provide that certainty, pushing the economy onto “a superior equilibrium”. Tariffs can even have their place as a strictly temporary measure, sheltering infant industries until they are ready to complete globally.

Doing industrial policy well is, of course, supremely difficult, requiring thoughtful strategy, total transparency about government-business linkages, and disciplined leadership. But this is not – to state the blindingly obvious – the way that Trump does things.

His erratic, vengeance-based approach to trade and economic development will, in precisely the way that conservative economists predicted, create all manner of problems. And, along the way, tarnish the reputation of a policy that should have much to offer progressives – and indeed the world.

The Spinoff: Is political trust ‘in crisis’? It depends

Trust was at its highest point just a few years ago, though we can’t be complacent.

Read the original article in the Spinoff

A few years ago, trust in New Zealand’s government was higher than at any other time in the last 35 years. Why, then, do we hear so much about a “crisis” of political trust? Obviously, trust matters: it is the glue that holds society together. Communities become dysfunctional when people cannot, as a rule, rely on their neighbours to behave predictably. Business transactions become near impossible without a basic assurance that others will follow ethical norms. And a populace can become ungovernable if it no longer trusts those doing the governing. This is not to say that full trust is desirable: surveys showing 100% confidence in government are a mark of authoritarian, dissent-suppressing dictatorships. Some measure of distrust is healthy. But very low trust is corrosive.

To see what that looks like, cast your eyes over the calamitous decline in the number of Americans who trust their government, now numbering just 20%. No wonder so many Americans are willing to back Trump.

New Zealand’s situation, however, is very different. In a master’s thesis published in February, Victoria University student Oliver Winter compiled data from surveys dating back to the early 1990s. What they show is a long-term increase in trust.

Note: the surveys graphed here are the World Values Survey (WVS), International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), New Zealand Election Study (NZES) and the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies (IGPS) trust survey

By 1999, New Zealanders were – as other surveys at the time make clear – reacting to 15 years of often undemocratic change carried out by governments intimately entwined with big business interests. But the introduction of MMP, and Helen Clark’s ability to hold corporate interests at a greater distance, helped restore some measure of confidence.

A slight decline in trust may have occurred under John Key, before trust spiked – as it did in many other countries – during the early days of the pandemic. The equivalent charts for parliament and the courts – equally important political institutions – show a similar, indeed slightly more positive, long-term trend.

This story comes, however, with two big caveats. The first is that the rise has been from a low base. The second and more serious caveat concerns the last few years: a return to pre-pandemic levels of (dis)trust can be seen even by 2023, and the data since then has only worsened.

The Edelman Trust Barometer survey, carried out late last year, shows a continued decline in trust. Relatively little weight should be placed on New Zealand’s underperformance versus the rest of the world, as Edelman surveys just 28 countries with wildly varying political setups.

More worrying is the fact that, as indicated by the circled numbers at the base of the blue bars, trust has continued to fall in all major institutions, and in the case of government is now below 50%. The slight downward trend detected in Winter’s work appears to have accelerated.

What is going on? Scholars in this area distinguish between weather and climate: changes in trust can be short term, transient responses to current events, or they can represent a shift to a permanently different environment.

It is plausible that New Zealand’s current decline in trust is just a form of weather. Evidence for this argument would include the lingering effects of the pandemic (which may well fade with time), the cost-of-living crisis (already easing, though certainly not over), and the confidence-sapping decline in the performance of our education and health systems (serious but eminently solvable problems).

Much angst has also been created by successive governments’ failure to fix apparently intractable economic problems, including crumbling infrastructure, rampant house price inflation and unchecked oligopolies. But current moves – including tentative steps towards bipartisan infrastructure investment, rezoning of large swathes of land for housing densification, and threats to break up the supermarket duopoly – hold out the promise of these problems being addressed.

We would not want, however, to put too much faith in such arguments. Distrust is not driven solely, or even mainly, by governments’ failure to deliver. Research suggests it is greatly amplified by economic disparities, which rightly lead the poor to believe that the rich have everything locked up, and people’s sense of not being heard by decision-makers. This entwining of poverty and political exclusion can be corrosive.

In a 2022 OECD survey, trust in parliament was 60% among financially secure New Zealanders, but only 40% for people struggling to pay their bills. Relatedly, just 35% of the poorest New Zealanders felt they “have a say” in political decisions. Across the whole country, barely one-third of us believed that if we took part in consultations, state agencies would listen.

So what would ensure the weather of distrust doesn’t become a climate of toxic disaffection? As a recent OECD report put it: “People need to feel trusted by the government in order to trust it.” The same report produced evidence that the most trust-enhancing reforms are those that ensure citizens’ voices “will be heard”.

That requires us to tackle the corrosive intersection between poverty and political exclusion: lifting living standards for the worst-off, clamping down on the channels (notably lobbying and political donations) that allow vested interests to convert money into power, and – above all – doing government differently. We need to bring politics closer to the people, giving citizens greater opportunities to be meaningfully engaged in shaping political decisions.

That could be as simple as doing consultation better – early enough that people’s input can shape the final result rather than being a tick-box exercise, and with officials going to the venues – shopping malls, sports clubs and so on – where people already are, rather than expecting people to come to them. It could also involve things like citizens’ assemblies, where representative groups of ordinary people are brought together to debate and find solutions to issues on which conventional politics has become logjammed, or participatory budgeting, in which local councils put up a proportion of their infrastructure budget for the community to discuss and allocate.

Either way, there is no need yet to panic about trust. We start from a much higher basis than many other democracies. We do not yet have hard evidence that we are in a permanently new climate of distrust rather than just a localised depression, to use the meteorological term. As the economist Shamubeel Eaqub has said in a recent report on social cohesion, we are “fracturing, not polarised”. But that still points to a country heading in the wrong direction, even if not yet arrived in the darkest place. We cannot be complacent.

The Post: Rearranging the road cones while workers are dying weekly

The health and safety minister’s decision puts corporate profits above lives.

Read the original article in the Post

In New Zealand one person is killed at work every week. In the same period, 10 people die from work-related illnesses like asbestosis. A further 700 sustain an occupational injury so severe that they’re off work for at least seven days.

Thank god, then, that the minister for health and safety is maintaining a laser-like focus on road cones.

Brooke Van Velden, who doubles as ACT’s deputy leader, announced this week that the regulator, WorkSafe, would oversee a hotline where the public could report “overzealous” road cone use. This shift of resources, from preventing deaths to monitoring orange cones, feels like a grotesque joke, the sort of thing even satirists couldn’t invent.

Van Velden’s announcement cited no evidence of any damage caused by road cones. As outlined in a recent report for Auckland Council, there are problems with roading contractors taking up too much space – for too long – with their traffic management systems, of which road cones are one part. But to solve this problem, the Ernst and Young report argues, councils need the power to levy steeper fines on errant contractors – not some daft hotline.

Coming from a party that derides “virtue signalling” and proclaims its allegiance to “evidence-based” policies, the hotline plan is the worst kind of empty, performative, evidence-free politics. It plays well with the angry older voter for whom road cones are merely the locus of a wider hatred of cycleways and other forms of progressive change, but does absolutely nothing to save lives and keep people safe at work.

The road cone obsession doesn’t even make financial sense. While ditching a few cones might at best save millions of dollars, the annual cost of our appalling health and safety record – the lost productivity from bodies dead and mangled – is, according to business leaders, at least $4.9bn. When questioned in Parliament, Van Velden admitted she has no proof her reforms will reduce this cost in any shape or form.

More troubling still is the human toll embodied by all this misery and death. Maybe the minister should familiarise herself with WorkSafe’s Fatalities Summary Table, a rollcall of workplace deaths detailed in language both spartan and sad: ‘quad bike rollover’, ‘forklift incident’, ‘fall from aerial work platform’, ‘crushed by falling object’, ‘trapped/caught in machinery’.

If anyone thinks that this is just how things are, that some occupations are unavoidably fatal, they’re wrong. Adjusted for population, deaths at work here are three times those in the UK, twice those in Ireland and Norway, a third higher than in Australia. We sometimes laugh at the UK and its pedantic, rule-obsessed, ‘elf and safety gone mad’ culture. But maybe there’s something to be said for laws that – you know – stop people dying at work.

Even Van Velden’s decision that some small businesses can focus only on “critical” risks is a classic case of something that sounds like common sense but falls apart on closer examination. The minister has suggested that those small businesses won’t have to manage things like psychosocial or ergonomic risk.

But as the Institute of Safety Management has pointed out, mental health and musculoskeletal disorders are the two main causes of workplace harm, accounting for twice as much damage as acute injuries like broken limbs. And smaller firms have higher rates of injuries than larger ones. As compliance costs for businesses fall, so will the costs to the nation rise.

Not helping matters are the government’s cuts to WorkSafe, where around 170 jobs have gone. Among its notional workforce of 675, some 200 positions remain unfilled, the Public Services Association reports.

Staff turnover is immense, not least because of the vast workload each inspector bears and their relatively poor pay rates. Investing in this workforce – rather than asking them to monitor road cones – is what’s actually needed.

Not that this registers with a minister now fully detached from the political mainstream. When she started wondering aloud last year about a “first principles” review of the 2015 Health and Safety Act, everyone who matters – including Business New Zealand, the Employers and Manufacturers Association, and the Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum – wrote an open letter pointing out that this would, in fact, be a total waste of time. The act is fine: it’s just not being enforced.

The great irony is that it’s not as if the coalition is incapable of governing well. Finance minister Nicola Willis’ intensifying attacks on the supermarket duopoly, and her recent threats of real action, suggest a politician in tune with both evidence and public mood.

Van Velden and her ACT colleagues, though, could block any supermarket break-up. Nor should we be surprised. Taking pro-duopoly positions, just like emphasising road cones over workplace deaths, is standard procedure for a party that has always put corporate profits above the welfare of ordinary folk.

The Spinoff: Note to ministers: cutting services doesn’t make need go away

Instead, it just shifts the needs onto others.

Read the original article in the Spinoff

When even employers are complaining about public service cuts in the National Business Review, the organ of the country’s corporate elite, it’s a sign that the shortcomings of the government’s cost-cutting agenda are spreading far and wide.

Under the headline “Lengthy mediation delays forcing employers to go private”, the NBR reported that “extensive funding cuts” at the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE), combined with increased demand, were causing “a lengthy backlog to access the country’s employment dispute resolution service”. And it’s a similar story across the country.

The number of people in emergency housing declines; the number of people sleeping on the streets increases. Emergency grants from Work and Income become harder to get; charity-run foodbanks have to hand out more parcels. State-funded social services retrench more generally; everyone else has to pick up the slack.

As the government is rapidly discovering, cutting back public services does not – astonishingly enough – make the need for those services go away. It simply shifts that need somewhere else.

National’s push to end emergency housing, for instance, has genuinely seen hundreds of people settled in state homes (that Labour built). But it has also driven more people onto the streets. In Wellington, the Downtown Community Ministry, which works with local homeless people, says the number of people rough sleeping in December 2024 was up by one-third compared to the year before. The ministry’s Natalia Cleland told RNZ that the criteria for getting emergency housing had been toughened so much that people had even “stopped asking”.

Another charity worker, Cindy Kawana from Auckland’s E Tipu E Rea Whānau Services, said she knew of one young couple using a hospital as a night shelter. “Them and their baby were sleeping in the emergency waiting room at night, so they had a roof over their head and it was safe and warm, and were in the park during the day, and they couldn’t even get onto the housing register.”

The government’s cutbacks are an attempt to shrink our sense of what constitutes the public good – the set of interests we share as citizens, as opposed to the varied and individual interests we pursue in private. This seems deeply misguided.

Being able to access publicly provided mediation services, for instance, certainly delivers a private benefit to employers and employees, but it is more fundamentally a public good – something that is in all our interests – for such disputes to be resolved with relative ease and speed, without a long and costly court process. Ensuring everyone has enough to eat, including via foodbanks if need be, is also a basic public good: we are all diminished if others go hungry, and we pay the long-term costs – in rising ill-health and falling productivity – when they do so. (Of course it would be better if paid work and welfare benefits covered people’s grocery shopping in the first place, so that foodbanks were not needed.)

Note that this is a question of funding, not service devolution. The government could legitimately take the view that some charities are better placed to deliver than central government agencies, and shift funding accordingly. But that is not what is happening. Funds are simply being removed.

Nor is this an issue that solely affects the poor and the weak: it has consequences for the middle classes. In opposition, National promised it would “co-invest” alongside councils to deliver new water infrastructure as an alternative to Three Waters. The government having backtracked on that pledge, councils are being left to bear more of the cost themselves: hence, in part, why rates bills are rising so rapidly. (Decades of under-investment are, of course, the principal villain – another example of costs being illegitimately shifted, in this case from one generation of ratepayers to the next.)

It’s the same story with items like vehicle registration fees (increased by $50 by National) and drivers’ licence re-sit fees ($89, removed by Labour but reintroduced by National). Your taxes may be lower than they would otherwise have been, but your user charges will be higher. Again, this goes against the public good: registering a car and re-sitting a test undoubtedly bring private advantages, but by far the most significant benefits – safe cars and safe drivers – are to the public as a whole.

The sad thing is that National could probably have reduced spending without harming public services. One public servant recently told me that, because there certainly was wasted spending, her department could have cut around 5% from its baseline had it been allowed to carry out a considered search for efficiencies over a year or so. Instead it got hit with a blunt 6.5% reduction target delivered at breakneck speed.

The same has been true across the public service, hence the cuts – proposed or actual – to climate change modellers, officials who help track down child pornographers, and countless other valuable staff and programmes. The vast majority of health-sector workers (in an admittedly self-selecting poll) recently said they had seen service cuts – something that is, of course, forcing people to turn to the private sector. Cutting the police’s backroom staff just means frontline officers have to spend more time filling out paperwork.

None of this generates productivity, efficiency or service improvements. It doesn’t make need go away. It just shifts the burden onto other people – often those least able to bear it.

The Post: The economic recovery should start at home

National’s economic pitch, overly focussed on foreign investors, opens space for a progressive economic nationalism.

Read the original article on the Post

“I care little for the mere capitalist.” Such were the stark words of John Ballance, newly elected prime minister in 1891, as he faced down parliamentary criticism of his economic policy.

He told the House: "I care not if dozens of large landowners leave the country. For... the prosperity of the colony does not depend on those classes. It depends upon ourselves, upon the rise of our industries and upon markets being secured in other countries, and not upon any such fictitious things as large capitalists or large landowners remaining in or leaving the colony.”

History, as they say, doesn’t repeat but it does rhyme. And it’s hard not to hear echoes of that century-old debate in our current politics.

Last week’s much-touted “investment summit”, in which the Government sought foreign investors for our infrastructure projects, cemented an impression I had long been forming. Too much of the coalition’s economic pitch, I think, consists of this point: “We need overseas heroes to save us.”

Of course that’s not all there is to it. Reforms in schooling and land zoning, for instance, will lift skills and help shift investment away from residential property.

Nonetheless the appeals to foreign investors are constant. It’s not just the investment summit: we’ve also seen visa reforms for overseas financiers, changes to the Overseas Investment Act, and a drumbeat of support for public-private partnerships.

Foreign investment makes good sense where it brings otherwise unobtainable skills and knowledge into Kiwi firms. But that’s not what will necessarily result from reforms that allow overseas investors to just park their money in government bonds. Foreign investment can also see profits sent offshore, or control of strategic assets lost.

Nor are those investors a magic money tree: they always have to be repaid somehow. And if, as is generally the case, they face higher borrowing charges than do governments, we’ll end up paying more in the long run.

Such deals make even less sense when – as Kiwibank’s Jarrod Kerr points out – the government could double its currently low debt levels without troubling the markets.

National is, more generally, prone to implying that our economic success hinges on a handful of “self-made” entrepreneurs. All of which creates an opportunity for Labour. To draw a contrast with this adoration of millionaires, the party could rest its faith on something humbler and more home-grown: the country as a whole.

What if, after all, we slashed our child hardship rates, currently sitting at 13%, to just 4-5%, as in the Netherlands and Finland? Socio-economic status, the evidence shows, is by far the biggest factor in school attainment. It’s hard to succeed in a cramped, dangerously mouldy house, with insufficient food and nowhere quiet to do homework, and with parents experiencing the toxic stress of unpaid bills piling up.

Just think how many more entrepreneurial talents we would unleash if we lifted all those children out of poverty. Think, too, how many more world-leading companies Kiwis would launch if the government doubled funding for blue-skies research and development, lifting it to the OECD average.

Think, finally, of all the extra people who could contribute economically if we provided better skills training for welfare recipients wanting paid work. This is, again, an area where we spend half as much as our developed-country counterparts.

The prize, in short, is an economy based on backing one another, on believing that if we invest enough in the vast mass of ordinary New Zealanders, innovation and dynamism will spring up. This is what Ballance meant when he said our economic future depends “upon ourselves”.

You could call it investing in people; some call it bottom-up or middle-out economics. It’s an approach that doesn’t close the door on beneficial foreign investors, but which holds that the largest difference will come from uplifting the people already here.

Where would we find the money to invest in ourselves? Close to home, again. We could build pools of national wealth through a Kids KiwiSaver scheme, in which the state enrols every child at birth and matches small contributions from parents. We could increase adults’ KiwiSaver contributions. Or we could, as Winston Peters suggests, create our own sovereign wealth fund.

Speaking of New Zealand First: a little bit of progressive economic nationalism – as opposed to the ugly Trumpian kind – would help Labour cosy up to Peters’ party, should it want more potential coalition partners.

Could this agenda succeed politically? Ballance would have said so. By 1891, he had introduced the country’s first taxes on income, much as Labour is now gearing up to propose a capital gains or wealth tax. This helped fund his drive to build the economy from the bottom up, using state money to assist ordinary people to acquire small farms.

All this “met with considerable criticism both at home and overseas”, Ballance’s biographer Tim McIvor wrote. But, he adds: “This was largely silenced when the premier announced a record budget surplus in 1892.” Having helped lift the country out of its long years of depression, Ballance was – in our drought-prone country – known forever after as “the Rain-Maker”.

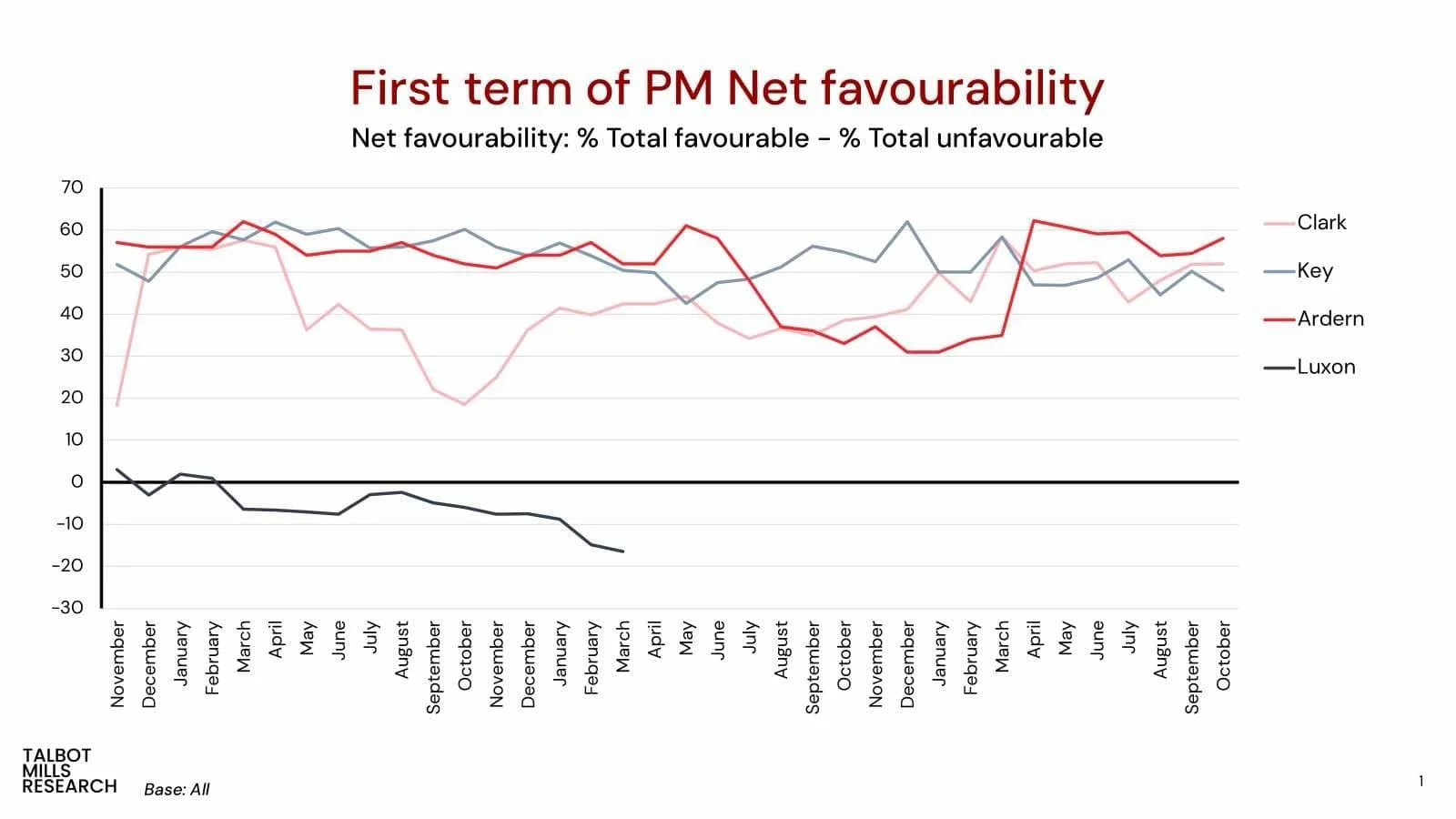

The Spinoff: Luxon’s epic unpopularity in one chart

Whereas previous leaders scaled the peaks of popularity, the PM is plumbing new depths.

Read the original article in the Spinoff

Everyone knows Christopher Luxon is unpopular. National’s polling is poor, and his preferred prime minister rating is now below that of his opposite number, Chris Hipkins, despite the latter’s deliberate strategy of being largely invisible for the last 18 months. There is even talk – although no more than that – of a challenge to Luxon’s leadership.

The extent of the PM’s unpopularity, however, has never been more clearly revealed than in the graph below, supplied to The Spinoff by polling firm Talbot Mills Research. It charts the net favourability – the percentage of voters who have a favourable impression of the prime minister, minus the percentage who have an unfavourable one – of our last four leaders during their initial term in government, from Talbot Mills/UMR polling over the years. While Helen Clark, John Key and Jacinda Ardern were mountaineers scaling the peaks, Luxon is plumbing new depths.

Every leader has their challenges, of course. Clark’s popularity dropped away in her first year, owing perhaps to the business revolt sometimes dubbed the “winter of discontent”, before recovering strongly. Ardern’s rating fell spectacularly amidst the failure to deliver the much-touted “year of delivery”, her status rescued only by a successful response to the pandemic’s initial onslaught. Even Key, largely serene, had a mid-term dip. Still, the paths of those three leaders could not be further from the one Luxon is treading: he started out unpopular, and has only become more so over time.

Everyone has their own theory as to why this is, but one common thread in the criticism is Luxon’s inability to articulate clearly what he stands for or what, at its best, this country could be. This leaves voters unmoved, their emotions detached from the prime minister and his prospects. As Duncan Garner recently pointed out, in a column predicting Luxon would be rolled before the next election, previous leaders have always had at least one group of hardcore fans. “Luxon can point to no such base of support,” Garner wrote, “even among the business community who must surely be wondering when [he] is actually going to do something.”

The point is borne out by new data from the Acumen Edelman Trust Barometer, which shows high-income Kiwis dramatically losing faith in the coalition. (Their low-income counterparts remain stubbornly distrustful of all governments.) This decline in trust appears to be evenly split between left-wing and right-wing elites, suggesting the latter are indeed disappointed with Luxon’s performance. While one can only speculate as to their reasons, they may include a distaste for the culture wars that the prime minister is allowing his coalition partners to pursue, a sense that his government has few real solutions to New Zealand’s long-term productivity problems, and the above-mentioned absence of vision.

All leaders, of course, eventually lose their shine. Some commentators perpetuated the myth of Key’s “incredible” popularity, but by the time of his resignation he had ended where Luxon began, at net zero, his detractors just as numerous as his supporters. The flag referendum debacle, the bizarre ponytail-pulling incident, the fact that leadership strengths inevitably turn to weaknesses: all these factors, and more, eroded his public favourability. Only the perceived unpalatability of his opponents, Phil Goff and David Shearer among them, propped up his preferred prime minister rankings.

Clark, supposedly less charismatic than Key, in fact stayed popular for longer than her successor did. But even she was near net zero by the end of her prime ministership.

Luxon’s defence, if there is one, is that the process of popularity decline is being hastened worldwide by an increasingly disgruntled, restive and febrile electorate. Britain’s Keir Starmer has barely got his feet under the table but already suffers catastrophically bad ratings. Across the ditch, Anthony Albanese could be about to lead the first one-term Australian government in a century.

Closer to home, and further back in time, Ardern’s popularity in her second term was – as has been extensively canvassed – in freefall. Like Clark and Key, she reached net zero, but within two terms rather than three. In democracies, public unhappiness now operates at something close to warp speed.

Arriving onto this increasingly chaotic stage, Luxon has, in one sense, been dealt a tough hand. Nonetheless he has not played it well, at least in the public’s opinion. Can he recover? In politics nothing should ever be ruled out: a recovery in the economy and improvements in public services – assuming either materialises – would certainly help, as would a bit more of what the first George Bush called “the vision thing”.

Trust, though, is famously hard to establish and easy to lose. What prospects, then, for a man who never had it in the first place?

The Post: The dismal revelations at the heart of Wellington Water debacle

The organisation’s chairperson, Nick Leggett, also has a major conflict of interest.

Read the original article in the Post

If you have tears of rage, prepare to shed them now. This week’s reports into the Wellington Water debacle contain some of the most infuriating, dismaying and jaw-dropping details of public-sector weakness this country has seen in some time.

Owing to the deals that Wellington Water entered into with a handful of contractors, ratepayers have – according to investigations by infrastructure consultants Aecom and the business consultancy Deloitte – been paying three times more than they should for repairs. Understandably outraged, local councillors are calling for a forensic audit of any potential “price-gouging”.

The reports reveal that Wellington Water – a utility owned by the region’s councils – was far too close to, and indeed calamitously reliant upon, the contractors it was supposed to oversee.

Rather than tender each piece of work to a full field of companies, Wellington Water created “panels” of three pre-approved teams of contractors, among whom the work was allocated. A further “maintenance alliance” effectively embedded another contractor, Fulton Hogan, within the utility.

Accordingly, Deloitte found, Wellington Water focused on “trust” and “partnership” with its contractors, rather than trifling things like competitive tension. Effectively, this “prioritise[d] … consultants and contractors over ratepayers”.

And it gets worse. As Wellington Water’s new chief executive, Pat Dougherty, has admitted, the utility had “consultants managing other consultants”. Some consultant managers were – unbelievably – asked to oversee the work of their own firms.

Before seeking bids, the utility sometimes told contractors exactly how much money was available for projects. How astounded its staff must have been, then, when the bids kept coming in high rather than low!

Ominously, Deloitte also noted concerns that the main contractors were not just charging Wellington Water their own overheads but also requiring the utility to pay the overheads of sub-contractors – effectively a form of double-charging. Local councillors suspect this is happening on other big projects.

And if you think you’ve seen this movie before, you’d be right. Two decades ago, a wastewater project in Kaipara blew out spectacularly, costing locals tens of millions of dollars. One of the failure’s root causes, the Auditor-General found, was a local council so short-staffed, so reliant on consultants, that it could no longer even manage its own contracts.

Likewise Wellington Water, which didn’t have its own system for managing pipes and other assets, but instead used systems supplied by, among others, Fulton Hogan, the very firm it was supposed to oversee. This, as Dougherty told local councillors last year, became an obstacle to pushing contractors for savings: “It is a little bit difficult to have terse conversations when we are absolutely reliant on their goodwill.”

This whole sorry saga is yet another indictment of the belief that paring back public bodies generates efficiency and saves money. By rendering those bodies hopelessly dependent on contractors, it does exactly the opposite.

The hollowing-out of Wellington Water ultimately stemmed, some argue, from underfunding by its shareholding councils. But given how the utility was run, why would they have coughed up more cash?

Either way, the obvious first step for Wellington Water – and any successor organisation – is to rebuild its core capabilities, and to treat contractors not as trusted “partners” but as what they really are, profit-hungry entities to be kept on a very short leash.

Whether the utility can do so under the leadership of its current chairperson, Nick Leggett, is another question. With some honourable exceptions, strikingly few people have noted Leggett’s conflict of interest.

In his other life as the chief executive of Infrastructure New Zealand, a body that lobbies for a bigger role for its corporate members, Leggett has his salary paid by – among others – Fulton Hogan. Not only that: the board to whom he reports includes Ben Hayward, chief executive of Fulton Hogan.

Other Infrastructure New Zealand members, including the engineering firm Beca, have had contracts with Wellington Water. Yet these are the firms whose work Leggett is supposed to control.

Some minor conflicts of interest can be handled by an individual “leaving the room” during specific decisions, but in this case, the issues with contractors – Fulton Hogan in particular – are threaded right throughout the organisation.

Leggett said this week that he had been managing the conflict of interest, and he was not involved in contractor discussions. But with all due respect to him, the conflicts of interest here look unmanageable – yet another instance of New Zealand not being tough enough on such relationships.

Leggett has, to his credit, acknowledged Wellington Water’s failings this week, and is putting more work out to open tender. But this is rather late in the day. A board member since April 2022, he was present in 2023 when the utility was warned of many of the above problems but dismissed them as, in the words of its then-chief executive, “a distraction”.

In its pursuit of better value for ratepayers, Wellington Water urgently needs to reset its relationship with contractors – and to have the public’s confidence that it has done so. It is hard to see how this can be achieved by an organisation helmed by someone who is paid by, and reports to, those very same contractors.

The Spinoff: We need to stop shadow-boxing on competition

Putting industries “on notice”, over and over, achieves little.

Read the original article on the Spinoff

When, earlier this month, finance minister Nicola Willis warned our uncompetitive supermarket duopoly that they had been put “on notice”, Foodstuffs and Woolworths must have been trembling with fear. Indeed they can barely have recovered from the shock incurred the last time they were – according to RNZ – put “on notice”, in August last year, for routinely over-charging customers. This came on top of the mortal peril of – you guessed it – being put “on notice” in 2022, this time by Labour’s David Clark.

During his 2022 press conference, Clark insisted that the supermarkets’ uncompetitive behaviour “can’t be kicked down the road”, while in the same breath announcing “another review of competition in three years’ time”. Black comedy aside, the wrenching incompatibility of these two statements hints at the reason why our supermarket giants may not, in fact, have collapsed in terror. They have correctly deduced that all this half-hearted making of threats, all this putting “on notice”, amounts to nothing whatsoever.

In a similar boat are our cartel-like banks, who have somehow mysteriously survived being put “on notice” not only by the current government (the National Party in December last year: “The big banks are on notice”) but also by its predecessor (Kris Faafoi and Grant Robertson in November 2018: “Banks [are] on notice to lift their game”). The banks have also bravely endured the finance minister’s rapier-sharp wit, shrugging off her carefully crafted description of their industry as “a cosy pillow fight” where other firms might have crumpled under this near-mortal blow.

Customers, meanwhile, await action. The Commerce Commission has calculated the supermarket duopoly extracts $1m in excess profits every day – profits, in other words, above and beyond those they would make in a competitive market. That $1m a day comes straight out of shoppers’ wallets. Kent Duston, the convener of the Banking Reform Coalition, estimates that another $10m a day in “unearned and unjustified profit” is extracted from us by the four big Australian-owned banks. A small handful of firms likewise dominate – and earn excess returns from – electricity generation, building supplies and other markets, many of which have also been put “on notice” to equally little effect.

Why is there so much shadow boxing, and so little action? One major culprit is the hands-off approach to regulation that has haunted the English-speaking world for decades. Anti-monopoly regulations should theoretically be popular even among small-government types: competition is, after all, the only thing that makes markets work. Monopolies, duopolies and oligopolies – the latter denoting market dominance by a handful of firms – are a menace to consumers, raising prices and squashing innovation. But even pro-competition regulations have long been deemed suspect.

The dominant view has instead stressed the economies of scale that – in theory – accumulate in larger firms. The mere possibility of competition, what’s more, is supposed to put a check on monopolistic behaviour. Obviously this latter idea is self-serving – or, rather, big-business-serving – nonsense, but it has nonetheless been hugely influential. Hence New Zealand has long tolerated two supermarket chains having over 80% market share, while further afield Facebook was – to take just one egregious instance – allowed to buy up both WhatsApp and Instagram.

Overseas, the grip of this laissez-faire view is weakening: witness the US Justice Department’s determined prosecution of Google’s monopolistic behaviour, and the tougher approach to anti-competitive activity crystallising within the European Union. Even in sleepy old New Zealand, everyone can feel the pressure build. It is not hard to guess why Willis has started talking a good game on competition: people don’t like the banks very much, and they really don’t like the supermarkets. Having a go at those firms – and their uncompetitive colleagues the electricity gentailers – is a free hit.

Our current politicians have, however, an immense fear of taking risks. No matter how angry the public gets over excess profits, there is far less peril in making big-sounding statements – and taking small, ineffectual steps – than in implementing the weighty structural reforms that would actually drive change. Decisively shaping markets feels like a step into the unknown; the possibility of a botched effort looms large. Hence, when it comes to the supermarkets, Willis has done nothing more than talk vaguely about removing “unnecessary regulatory hurdles that discourage new entrants”, whatever those may be, and taking further steps that “could” – note the hesitant conditional tense – include helping new entrants access suitable land.

It doesn’t help that there is no clear consensus on the exact remedies for anti-competitive behaviour – which may vary from sector to sector – nor much detailed academic work on how to implement them. Several influential figures have called for the gentailers to be broken up, so that they can no longer exploit the commercial advantages of being able to both generate and retail electricity, but it is unclear just how much good this would do.

When it comes to the supermarket duopoly, a third competitor might be encouraged – but how? Some credible thinkers – among them the Australian competition expert Lisa Asher – argue New Zealand is badly under-served with supermarkets. Others, such as 2 Degrees founder Tex Edwards, believe that on the contrary New Zealand is “oversupplied”, and that the only solution is to force Countdown and Woolworths to divest 140 of their existing stores to a new entrant. Other thinkers on the progressive left are arguing, at least in private, that tougher regulation of the current supermarkets – rather than a new competitor – is the way to go.

Questions abound, too, about whether our entire legal framework on competition is fit for purpose. Clarity on all these points will be needed before the next election. Because right now, when it comes to tackling anti-competitive behaviour, New Zealand politicians are locked in a pointless cycle of empty words and signals of virtue. For the sake of the consumer, they may need to stop handing out “notices” that are about as threatening as a wet wipe, and start taking action.

The Post: Labour’s patchy poverty record eases pressure on National

Progress on tackling hardship must be revived, after stalling recently.

Read the original article in the Post

Not met. Not met. Not met. The rollcall of verdicts on the last Labour government’s progress against its child poverty targets, released by Statistics New Zealand on Thursday, was unsparing. The party didn’t meet a single one of the goals it had set for its first – and, as it turns out, only – two terms in government.

Labour had, of course, a hard road to travel. Although some measures of hardship fell under John Key, his National government had spent much of its time claiming it couldn’t even measure poverty, let alone tackle it.

But determined campaigning by NGOs, amplified by hard-hitting reportage, had sparked public concern by filling TV screens with images of children growing up in mould-ridden houses where the heating was switched off to save money – homes where fridges were empty and hope in short supply.

In the 2017 election, Bill English and Jacinda Ardern vied to outbid each other on tackling hardship. And when she won power, one of her first moves was to pass the landmark Child Poverty Reduction Act.

Confronting a situation where, depending on the measure, somewhere between 150,000 and 250,000 children lived in hardship, Labour set itself the goal of cutting those rates by one-third by 2024 – and by as much as two-thirds by 2028.

So, what went wrong? Initially, not much. The party addressed the issue with seriousness, rigour and compassion.

In its first term, the Families Package put $1bn extra a year into the pockets of poor and middling households, via higher benefits and Working for Families tax credits. Poverty dropped sharply, and the number of households unable to regularly afford food fell from 20% to 13%.

Even in the pandemic, Labour achieved the remarkable feat of keeping poverty levels flat or falling, partly through continued benefit increases and wage subsidies. The problem was everything after.

To maintain progress on its chosen path, Labour would have needed another $1bn-a-year Families Package. But none was forthcoming, largely because there was no capital gains tax – or reprioritised spending – to free up the required funds. Compounding the problem, the cost-of-living crisis drove Labour to focus increasingly on the “squeezed middle”. It took its eye off the ball.

The ultimate verdict, as delivered on Thursday, was that Labour cut child poverty by just 30,000-50,000 on two of its key measures (and not at all on the remaining one). It missed its 2023-24 targets by about as much again: a job half done, in short. As many as 150,000-200,000 children remain in hardship.

There were wider failings, too. Labour’s goals were couched in impenetrable policy-speak: I defy any layperson to tell me what “50% of equivalised median household disposable income” means. Even Cabinet members couldn’t have explained targets that, unsurprisingly, had next-to-no public support.

Labour’s agenda also relied too heavily on benefit and tax-credit increases. These are important policies, but should the state’s coffers really have to do so much heavy lifting? If work paid better, employers would rightly shoulder more of that burden.

Alongside benefits and wages, a third big lever for tackling child poverty is housing, and here Labour’s record was once again mixed. State house-building, revived after lying dormant under National, added over 14,000 homes, while ramped-up infrastructure investments and zoning reform began clearing the way for increased affordable housing. More, though, was needed.

So where to from here? The pressure is, for the moment, pretty well lifted from National, which can use Labour’s mixed record as a get-out-of-jail-free card. And until middle-class families feel their living standards have recovered, they may have little compassion to spare for others.

Our best hope is that, if the economy can recover, so too will our reservoirs of sympathy. Pressure can still be applied to National to meet its own unambitious targets for 2027, which involve either maintaining the current rates or lowering them by just a few percentage points.

A new drive to halve child hardship – to lift out of poverty roughly 75,000-100,000 of the remaining 150,000-200,000 children – could be pencilled in for, say, 2035. Those targets would, though, need to be couched in one readily comprehensible measure, not to mention a wider national mission and sense of purpose that would excite public support.

We need, above all, a rethink of our social and economic systems, one based on acknowledging our responsibilities to each other – to poor children, in particular, who are blameless in their situation – and recognising that growth is best built from the bottom up. The only way to fix our productivity problems is to ensure that each of us is capable of paddling our collective canoe as fast as it can go. And that, in turn, will require us to make the collective investments – in health, in education, in housing, and in incomes – that will equip every child to play their part in that mission.

The Post: Government undermining house-building efforts of Labour regime

The capacity to build state houses efficiently is precious, and must not be squandered.

Read the original article in the Post

It was, in the words of one visitor, “kind of secret squirrel”. Although the Christchurch office building belonged to the Homes and Communities Agency, Kāinga Ora, no external signage acknowledged this fact.

Inside, staff had to switch off phones and emails. “I felt like I was entering MI5 or something,” this visitor tells me. Instead they found a room stuffed with every kind of housing professional – from architects to resource-consent experts to engineers – all plotting the delivery of state housing projects. On the walls, a stream of Post-It notes, each one representing a different stage of house-building, moved from left to right, the whole process designed to create a seamless, delay-free flow of tasks.

This work, carried out under the sci-fi-esque title of Project Velocity, became the more soberly named Housing Delivery System (HDS). But the goal remained: slashing the time and cost taken to build homes for the country’s most vulnerable residents.

It seems to have worked, too. The pilots reportedly cut construction costs by 40-60%, thanks to getting everyone in the same room at the outset, minutely planning workflows and avoiding ordering the wrong materials.

The usual building-site inefficiencies – notably, waiting for the right tradies to turn up at the right time – diminished sharply. Kāinga Ora claims labour productivity “doubled”, and former board member Philippa Howden-Chapman says the time between design and consenting fell from 17 months to just six weeks.

All this matters intensely in a week when the government launched a “turnaround” plan for state housing that looked more like “Project Managed Decline”. After completing Labour’s project pipeline, the government will cap the number of Kāinga Ora homes at around 78,000.

As the population – and thus housing need – increases, the proportion of that need that Kāinga Ora meets will slowly fall. Meanwhile NGOs – the other main provider – have funding to build just 500 homes annually for the next three years. Contrast this with Labour’s six-year tenure, when nearly 18,000 houses were added at an ever-accelerating pace.

National’s attempt to undermine this success takes two forms. The first is to complain about Kāinga Ora’s debts. But as Howden-Chapman noted last year, “Has anyone ever bought a house or built a house without doing any borrowing?”

The increased debt largely represents increased ambitions. It guarantees that future generations will pay their share of the investment in ensuring vulnerable people are housed. (Which, incidentally, saves a fortune in health and other avoided costs.)

Some of the debt, of course, might have been incurred because Kāinga Ora was inefficient. Finance Minister Nicola Willis claimed as much last year, saying its build costs were 12% higher than in the private sector.

But even National’s anointed Kāinga Ora chair, Simon Moutter, noted that private developers can “pick and choose” their sites, while his agency must work with awkwardly situated land. It also builds many disability-friendly homes and has sought the highest environmental ratings.

On an apples-for-apples basis, Kāinga Ora’s costs may be roughly the same as those of private developers. Of course, given its economies of scale and opportunities for learning-by-doing, Willis is right to say the state agency’s costs should be far lower. But HDS was starting to address that, and Moutter has a target to cut costs another 20%.

We must also remember that Kāinga Ora had to start almost afresh. Under the previous National government, more state houses were sold than built; a deficit of about 14,000 homes – relative to population growth – accrued, deepening the catastrophic sales under Jim Bolger in the 1990s. John Key’s government also did “almost no” renewals of ageing stock, according to Kāinga Ora.

Labour, in short, inherited a massive maintenance backlog and a state agency that had lost all knowledge of how to build at scale. This is one reason why left-wing governments often look “inefficient”: they have to restore so much depleted capacity before anything else happens.

In growing Kāinga Ora’s capacity ten-fold, and at high speed, Labour may have made mistakes, setting its remit too broad and creating a behemoth often unloved by local communities and even the more socially minded developers. But the party was responding to an appalling deficit in social housing, which is still just 4% of our housing stock when the developed-country average is 7%.

We need over 40,000 more social homes simply to reverse the cuts of the last 30 years and to house the 112,000 people living on the streets, in temporary shelter and in overcrowded dwellings. Curbing Kāinga Ora does nothing to solve those problems.

Still, even National’s steady-state solution involves building 1500 homes a year (counterbalanced by sales and demolitions). Selected staff including Caroline McDowall, the head of housing delivery, have been retained.

The best-case scenario, in short, is that Kāinga Ora maintains – or even sharpens – its capacity for delivering high-quality housing efficiently. Then it won’t be so painful for the next Labour government to scale it up again.