The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Newsroom: A big idea 4 — ‘A national holiday to talk politics’

A well-designed set of events, strong institutional support and public pressure would help create a culture of engagement.

Read the original article on Newsroom

Max Rashbrooke is a research associate at Victoria University of Wellington’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, and has recently published the report Bridges Both Ways: Transforming the openness of New Zealand government. This article sets out the fourth of five ‘big ideas’ drawn from the report, with the final one to follow shortly.

Many people want to know more about what’s going on in politics, take part in political discussions and vote in a more informed way – but lack the time, energy and space for it. And that’s understandable. With a record number of families having both parents in work, and New Zealand having long working hours in general, it isn’t easy to carve out time to think about the issues.

It’s also not something that everyone can do without a supportive environment. In the past many people were members of groups – such as churches or trade unions – where politics were regularly discussed. Those groups provided a bridge between individuals and the often complex and confusing world of current events. They created a space in which people could see politics being ‘done’ and in which they could take their first steps in that arena – but have significantly stopped performing that role.

All of which means we should think about ways to create new spaces and opportunities for people to discuss the big issues. One idea for doing that has been advocated for many years by two American scholars, Bruce Ackerman and James Fishkin. They call it Deliberation Day and the idea is that around two to three months before every general election, there could be a public holiday dedicated to discussing politics and the upcoming vote.

A New Zealand version, which we might call a Kōrero Politics Day, would ideally be marked by community events and working bees, town hall meetings, festivals that combine music and politics, and other gatherings designed to foster discussion. On the model of the annual Neighbours Day Aotearoa, every community could be given a small amount of funding to put on an event that would bring people together to discuss the issues. The idea would be to make talking about politics interesting or even, dare one say it, fun. Working it in around community events would also help make it more natural – a chance to chat while doing something together, rather than an excessively formal ‘debate’.

While political participation on the day could not, of course, be enforced – no more than people can be forced to think about the Treaty on Waitangi Day – it is likely that a well-designed set of events, strong institutional support and public pressure would help create a culture of engagement.

All of this would underline the importance of politics, give people time and space to think about issues, and encourage a more reflective citizenship – and therefore better political campaigning. The kind of campaigning that parties do typically responds to where they think the voters are at and how deeply they engage with the issues. Better informed voters would encourage campaigning that focuses more on the issues and less on the substance.

While political participation on the day could not, of course, be enforced – no more than people can be forced to think about the Treaty on Waitangi Day – it is likely that a well-designed set of events, strong institutional support and public pressure would help create a culture of engagement. As Ackerman and Fishkin have argued, evidence from deliberation-based events shows that “the public has the capacity to deal with complex public issues; the difficulty is that it normally lacks an institutional context that will effectively motivate it to do so”.

Since New Zealand elections typically happen in spring, a holiday a few months earlier would provide a much-needed break in the middle of winter. The Kōrero Politics Day could, as above, take place only in election years, but could also happen every year to emphasise all the important political discussions that go on outside of election campaigns.

An extra holiday would of course increase costs for business. But it would only bring New Zealand up to the G20 average of 12 statutory holidays a year, well below countries such as Finland on 15, so it doesn’t seem an excessive burden. And New Zealanders already work long hours: the main cause of the country’s relatively poor economic performance is not time away from work but a failure to be efficient and productive while people are at work.

An alternative with lower business costs would be to designate a Saturday or Sunday as the Kōrero Politics Day – but that might be underselling the importance of politics. New Zealanders often begrudge spending money on their democracy, but it’s actually one of the key underpinnings of our lives, and should be invested in. We don’t expect houses to last well if they’re built cheaply. So why should we expect our democracy to work well if we’re not willing to spend some money on it? A day for talking about politics would symbolise our commitment to this fundamental aspect of our lives – and go some way towards improving the standard of democratic debate in this country.

The state of poverty and inequality in 2017

New Zealand’s current level of inequality is roughly equivalent to its early-2000s level. But its long-standing nature actually makes it worse.

Today the Ministry of Social Development published its 270-page Household Incomes Report, the gold standard annual record of poverty and inequality in New Zealand. So what did it tell us? Below are four key conclusions I have drawn, based on pulling out a few key figures and graphs. The discussion is slightly technical, but as little as is humanly possible.

1. Poverty remains stable since the Global Financial Crisis

There are lots of different ways of measuring poverty, and they tell slightly different stories. But overall poverty seems to have been relatively stable since the Global Financial Crisis. For instance, the proportion of households living on less than half the national average (for households their size) was 9% in 2009, and 10% in 2016. The proportion of households living on less than 60% of the national average was 18% in 2009 and 18% in 2016.

Those figures are before housing costs are deducted. After housing costs are deducted, 14% of New Zealanders were on less than half the average income both in 2009 and 2016. Some 19% were on less than 60% of average income in 2009, and 20% in 2016.

For children, it is roughly the same story. Before housing costs, 13% of children were in households with less than half the average income both in 2009 and 2016. The equivalent figure for households with less than 60% of average income is 20-21% in both years.

After housing costs, 20% of children were in households with less than 50% of average income in 2009, and 19% in 2016. The equivalent figure for households on less than 60% of the average is 27% in 2009 and 25% today.

The stability of these poverty numbers reflects the fact that income increases for the poorest fifth of the country, at around 12% since 2009, are roughly the same as those for middle New Zealanders, so the poor are pretty well ‘keeping pace’. That also means that, relative to the poverty line ‘fixed’ in 2007, there are fewer poor households and poor children. (Since, however, I think the most important poverty measures are the fully relative ones that shift as average incomes increase, I have concentrated on those.)

The exception to the above story is for the more extreme poverty – children in households with less than 40% of average income, after housing costs. Those numbers have increased from 10-11% in 2008/09 to 13% in 2016 – an increase in actual numbers from 120,000 in 2009 to 140,000 in 2016 (and that figure had gone as low as 105,000 in 2008).

This may reflect the severity of the housing crisis for the poorest. Data reported in the media recently (not from the Report) also show increases in homelessness, rough sleepers, people using food banks, and so on.

In contrast, when it comes to material hardship measures based on asking families what they can’t afford, the rate for children in material hardship has fallen from 16% in 2009 to 12% in 2016. That covers the households missing out on 7/17 key items, such as being able to afford decent clothing. But the most severe rate of material hardship (missing out on 9/17 items) has also fallen, from 9% to 6%.

What is clear either way is that, despite some claims to the contrary, overall poverty numbers have not increased under the current government. But at the same time, our high levels of poverty (twice those of some European countries, especially for children) have not been reduced, and indeed, worryingly, seem to be becoming ‘baked in’ and normalised.

On an unrelated note, it remains the case that around 4 in 10 poor children are from households that have not had anyone on a benefit in the last 12 months. Work is clearly not sufficient for escaping poverty, despite the popularity of that idea.

2. Housing is important – up to a point

Housing is clearly a major concern at present in New Zealand. The Report has many figures on this, but perhaps the most striking is that the poorest fifth of the population are paying on average half their income (51%) in housing costs. The housing situation is obviously dire and needs urgent action, whatever one’s views about the best way to do that.

However, one must be careful about asserting that housing is the dominant factor in inequality. It is true that after-housing-costs measures of inequality have increased more than others since the GFC, and housing is obviously an important lens through which to see inequality at present.

But 18% of the population are poor (living on under 60% of average income) even before housing costs are taken into account (as above), and that figure increases only a further two percentage points, to 20%, after housing costs. My own rough estimate (set out here) is that, of the overall increase in inequality since the mid-1980s, only one-tenth can be attributed to increased housing costs.

Clearly, while housing matters, it is hardly the sole or even the main cause of inequality. Other issues – such as jobs, training, wages, benefits and taxes – are equally or more important individually, and clearly more important as a whole.

3. Inequality is up slightly since the GFC

The figures in the Report continue the story of recent years. On almost all the measures, one can see a slight rise in income inequality under the current government, enough to cancel out the slight fall under the previous government. The Gini coefficient graph (where 0 would imply income being equally shared and 100 would imply all income being held by one person) shows this clearly.

Because the rise under National cancels out the fall under Labour, New Zealand’s current level of inequality is roughly equivalent to its early-2000s level. (Describing it as ‘stable’, however, can be misleading, since policy changes, especially Working for Families, have both reduced and increased it in that time.)

Income gains have been reasonably even across the spectrum since the GFC – between 10% and 15% for most groups, with only slightly higher rates for the richest groups contributing to slightly increased inequality. Again, this is in contrast to some of the narratives around ‘skyrocketing’ inequality under the current government. Again, however, there is no progress on reducing inequality, and indeed the progress made under the previous government has been lost.

It is worth remembering that New Zealand experienced the developed world’s biggest increase in income inequality from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s. Since 1984, incomes have increased just 29% (after inflation) for the poorest tenth and 38% for the average person, but 96% for the richest tenth. Nothing has happened since the big rise in the 1980s and 1990s to rebalance the income distribution.

4. All these numbers need to be seen in the longer context

Some people will conclude from the above figures, especially those showing inequality still at its early-2000s level, that there is no issue (except the housing crisis). However, there is an equally good argument that the long-standing nature of these problems actually makes them worse.

Poverty has profound impacts on individuals, and inequality tends to damage the social fabric, increasing the social ‘distance’ between people and thus diminishing trust, cohesion, and so on. The fact that those problems have been left to compound for the last 20 years – and in particular have major effects on children that will continue throughout their life – arguably means they are worse than if they had just sprung up yesterday.

Newsroom: A big idea 3 — Let citizens draw up DIY Budgets

Give people enough time, and expert advice, and they will amaze you with the quality of the decisions they take.

Read the original article on Newsroom

Max Rashbrooke is a research associate at Victoria University of Wellington’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, and has recently published the report Bridges Both Ways: Transforming the openness of New Zealand government. This article sets out the third of five ‘big ideas’ drawn from the report, with the rest to follow in subsequent weeks.

Number three: A citizen-generated Budget

The Budget is the Government’s most important announcement every year. Which makes it our most important announcement as a public, as a group of citizens, since government is ideally nothing more than us acting collectively under a different name.

And yet we have very little say over it. Up to a point, that’s normal: when we elect politicians, we delegate certain decisions to them. But wherever possible, we could still be looking to take back some of those decisions for ourselves, or at least make our feelings known more clearly. We are also falling behind other countries. On the international Open Budget Survey, New Zealand scores well for publishing information about the Budget, but pretty badly – just 65 out of 100 – when it comes to allowing public participation.

One innovative way to change that would be to have an annual Budget drawn up by citizens – a DIY Budget, let’s call it – that would show the Government how people want their money to be spent, and force ministers to justify their decisions against it.

It would work using the internationally-recognised practice of a citizens’ assembly, in which a group of, say, 100 ordinary people, selected to be representative of the population as a whole by age, gender and so on, would be asked to gather over a couple of weekends, with payment for their time. The assembly would be asked to draw up a rough annual Budget, indicating their spending priorities – such as whether they want to see more or less spending in broadly defined categories such as health, education and defence – and what tax increases or reductions (again, at a broad level) would be needed in consequence. The assembly members wouldn’t have to get into the nitty-gritty of every Budget line and allocation, but they would have to make high-level calls about which spending areas are most important.

Give people enough time, and expert advice, and they will amaze you with the quality of the decisions they take.

To help them work through what would still be a reasonably difficult task, they would need to have available the best expert advice from political scientists, economists and financial modellers – people who know intimately how the system works, how spending decisions would have to be traded off, and the options for raising or cutting taxes. The DIY Budget would be published at the start of each year, to inform official Budget decisions and to force the Government to justify itself when its Budget diverges from the citizens’ version.

Think this all sounds far too complex and pointy-headed for a bunch of ordinary people? In fact, citizens’ assemblies overseas have handled much more complex (and, frankly, boring) issues, such as the design of new electoral and local government systems. Just across the Tasman, a 2015 citizens’ assembly of 43 Melbourne residents and business owners drew up a clear and rigorous 10-year financial plan for the city’s council. The plan was applauded for making a series of tough calls on potential new projects, the sale or retention of public assets, and the tax take needed in consequence. In other words: give people enough time, and expert advice, and they will amaze you with the quality of the decisions they take.

Like the earlier proposal in this series for citizens-generated laws, this idea wouldn’t hand over power to citizens in an uncontrolled way. The Government would still set the actual Budget, as indeed it must, given the way that document shapes all the rest of its agenda. But it would make the desires of citizens much, much more visible and clearer than they are now, and would significantly raise the bar (and the level of public embarrassment) for ministers who wanted to do something different.

The other advantage of this proposal is that, unlike in a referendum where people can vote on an issue in isolation, these kinds of assemblies force people to do the real work of politics, which almost always involves trade-offs: more money for something means less money for something else, or tax increases. The DIY Budget would also force people to put their money where their mouth is. In surveys, people always say they would like more spending on health, education, anything you care to name, but the suspicion is they aren’t actually willing to pay the tax needed to fund those increases. A DIY Budget would settle that question.

Newsroom: A big idea 2 — Let public vote on council budgets

The more closely people can control certain budget decisions, the better the quality of those decisions and the services that result.

Read the original article on Newsroom

Max Rashbrooke is a research associate at Victoria University of Wellington’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, and has just published the report Bridges Both Ways: Transforming the openness of New Zealand government. This article sets out the second of five ‘big ideas’ drawn from the report, with the rest to follow in subsequent weeks.

Number two: Direct voting on council budgets

Imagine if you could have a direct say over how your council spends its money – if you could get it to build that children’s playground your neighbourhood needs, or install lighting to make your area safer.

As it stands, you can put in a submission on your local council’s annual plan – if you get the chance – or you can lobby your ward councilor. But whatever voice you have in that process is one step removed from where the decisions get made.

Imagine if, instead, local councils put up 10 percent or more of their annual budget to be decided directly by you and your fellow members of the public. It’s a model that has worked well overseas, notably in Brazilian cities, and often goes under the slightly clunky title of participatory budgeting.

It’s not easy or cheap, of course. (But then why should democracy be cheap, when it’s one of the key foundations of our lives?) It starts with council officers going round their area, block by block, ward by ward, letting people know there is a big chunk of the annual budget up for grabs.

This culminates in a big end-of-year town hall meeting, where residents (or temporary representatives appointed for the occasion) vote to allocate the funds. The great thing about this process is that, unlike referenda where people can vote on issues in isolation, it forces citizens to make trade-offs. If they want more money for library upgrades, there will be less for swimming pools.

When these schemes have been used overseas, they’ve had proven benefits. For a start they get lots of people involved in politics – including people who’ve never been involved before, especially those living in poverty, although the poorest are often still not engaged.

In the Brazilian city of Porto Allegre, up to 40,000 people have been involved in the process each year. And as a result, the spread and quality of public services has increased: in particular, public services have been extended to cover those previously excluded from their benefits. Unsurprisingly, what councils deliver also better reflects what their citizens want.

These methods work best face-to-face – a lot of their magic resides in the interactions of citizens, in the moments when they confront each other’s views and have to justify their own. But that labour-intensive process can be supplemented by less demanding schemes – such as creating longlists of potential building projects for the public to rank online.

Why should democracy be cheap, when it’s one of the key foundations of our lives?

As with most schemes designed to create more ‘everyday democracy’, these direct budgeting ideas don’t aim to write local councillors out of the picture. For many reasons they will always remain important, and will have to make most key decisions. Direct voting on budgets is just designed to shift the balance a little in favour of citizens. And the evidence from overseas is that people are more than up to the task, if only they get the opportunity.

One of the big issues this idea would face in New Zealand is the limited power of our local councils. Because we have an exceptionally centralised form of government, our local councils don’t do many of the things – like running schools and health services – that their overseas counterparts do.

That means a lot of council spending goes on things like wastewater services where there isn’t much discretion, or a public interest, in shaping them. Those services, to a large extent, are what they are.

So direct voting on budgets would have to be adapted to local circumstances. It might be that it works better with those that, like Wellington City Council, have unusually large budgets and fund a wide range of projects. Or it might work better in smaller councils that are more flexible and naturally open to their constituents.

Or it could be that, instead of holding big town hall meetings, councils get citizens involved in different ways – for instance, by letting community boards or other organisations have more control over specific projects, such as upgrades to their local shopping area.

A final alternative: instead of accepting that councils have few powers, we could argue that a move towards participatory budgeting could be the spur for something that probably should happen anyway – the shifting of some services from central government to local councils that arguably have a better idea of what their residents want.

Whatever happens, the basic point is that the more closely people can control certain (though not all) budget decisions, the better the quality of those decisions and, ultimately, the services that result. In an era where people expect more control over their lives and more transparency than ever before, it could be a sensible reform for government to make and thus ensure that it keeps up with citizens’ expectations.

Newsroom: A big idea 1 — Crowdsource our laws

Why should we wait around for Parliament, when we have good ideas of our own?

Read the original article on Newsroom

Max Rashbrooke is a research associate at Victoria University of Wellington’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, and has just published the report Bridges Both Ways: Transforming the openness of New Zealand government. This article sets out the first of five ‘big ideas’ drawn from the report, with the rest to follow in subsequent weeks.

Number One: Crowdsourced bills

For most people, the process by which laws are made is a hopelessly arcane one. They have no idea how they might ever get involved in proposing or writing something that might one day become law. The procedures of Parliament are a complete mystery to them.

Of course, you could say that that’s what we have MPs for, and that’s true, up to a point. But they hardly have a monopoly on ideas for good laws, and there’s no guarantee they will think of everything that people might want put forward.

Fortunately, other countries have been thinking of ways to demystify the lawmaking process. Indeed some of the most exciting democratic innovations around the world involve the public in directly crafting and proposing legislation. One that’s worth looking at closely is Finland’s creation, around five years ago, of an online platform where citizens can propose laws that its parliament must vote on if they attract more than 50,000 signatures.

New Zealand could follow this lead by creating a secure online platform for people to put up their ideas for draft bills. That could be a bill for a ‘Google tax’ like the one Australia has, or to create incentives for local councils to free up land for housing, or to decriminalise abortion. Whatever people proposed, the form they’d fill out would require them to give reasons for their bill, cite evidence and carefully explain how it would achieve what they wanted. That would do a lot to deter trivial or poorly-considered proposals.

Why should we wait around for Parliament, when we have good ideas of our own?

A small number of the proposed bills would be selected each year to go before Parliament, via some kind of democratic process. It could be that, as in Finland, all those with the support of more than 1 percent of eligible voters – which in New Zealand would be around 35,000 people – could go forward, or Parliament could reserve a few places each year for the top-voted crowdsourced bills, as it does for the Members’ Bills put up by opposition and backbench MPs. And Parliament would have to give priority to crowdsourced bills, to ensure they don’t get put off forever while the Government gets its own bills through.

As with Members’ Bills, the selected bills would be passed onto the Office of the Clerk to be drafted and improved, as another quality check and to increase the chance of their being passed. And they would, if supported by MPs, go through the normal process of being examined by select committees and commented on in public consultation. There is, admittedly, no guarantee the bills would become law. But Finland has shown it can work – the bill that gave them marriage equality was a crowdsourced one. And what’s certain is that the process would force politicians to give the bills a fair hearing, and would raise the stakes for going against popular sentiment. Even when crowdsourced bills don’t succeed, they create valuable debate and lay the groundwork for later change.

Official drafting and Parliamentary sovereignty would play an important role in checking poorly-considered or illiberal measures. If, for instance, someone suggested bringing back the death penalty, or a law that would trample on the rights of minorities, Parliament would still be there to stop it going through. In any case, the Finnish experience shows people use the process to suggest pretty reasonable (though of course debatable) things, like tougher penalties for drunk driving and changes to copyright laws.

If implemented, this process could provide a more concrete target for petitions, which currently get handed to a select committee and then, usually, die a quiet death. Crowdsourced bills would largely do away with the need for citizens-initiated referenda, except where individuals wanted to show overwhelming public support for their proposal. But if they still went down that route, successful referenda could likewise generate a draft bill to go before Parliament. The crowdsourcing process could also work in tandem with methods where government departments create radically open places to debate or ‘crowdsource’ legislation, while retaining control of the progress of laws.

The Finnish experience shows these things can work. And, what’s more, they help people feel like they can ‘do’ politics. Research shows that the crowdsourced bill process can engage people who aren’t otherwise politically active, including those in marginalised groups. In short, it’s an easy way to demystify a complex process, and to bring the art of law-making within everyone’s grasp. MPs will always run most of Parliament’s business – but why should we always wait around for them, when we have good ideas of our own?

Why a referendum on smacking is a terrible idea

How does democracy protect the interests of those who don’t get a vote?

New Zealand First has just announced that it wants a referendum – another one, but binding this time – on our anti-smacking laws.

I’m not opposed to binding referenda in principle, although I do think they are the bluntest tool in the direct democracy toolbox, so you might think that I’d support this call.

I don’t, though, for several reasons. For a start, it’s been relatively recently debated, and settled, and there is no evidence for a need to revisit the issue. The police are not going around arresting thousands of people inappropriately or prosecuting parents for the kinds of force that are permitted under the act.

There is also the very strong evidence that physical punishment of children doesn’t work, and in fact is counter-productive, being liable to increase their levels of aggression later in life.

Most fundamentally, though, a referendum of this kind would strongly raise the question of who gets to vote. Most major issues predominantly affect adults, so it’s not really a problem that only adults vote. This issue, however, has huge consequences for children, yet they get no say in it. Even though there are extremely obvious, and generally unproblematic, reasons why children don’t get to vote, issues like this do raise a wider question. Namely, how does democracy protect the interests of those who don’t get a vote?

The same point applies, in a sense, to the environment, which obviously can’t ‘represent’ itself in a democratic process, and to future generations, who will be powerfully affected by our decisions now, and yet cannot influence them.

What society does in these situations, increasingly, is create bodies that can represent those groups. The Children’s Commissioner and the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment exist at least in part to create a ‘vote’ or ‘voice’ for otherwise excluded parties. In contrast, a referendum would do nothing to enhance the voice of children.

Referenda can also be dangerous because of the well-known potential for the majority to interfere with the liberties of the minority. In a country with strong constitutional protections for minorities, those dangers are minimised, but New Zealand does not have those protections. Again, there is great potential for the rights and interests of children, a very important minority, to be overridden in ways that are highly problematic.

In short, although an appeal to let ‘the people’ decide always sounds appealing, it is not always the right option, and certainly isn’t in this case.

Donations to political parties 2011-16

National dominates the fundraising stakes, while donations over $15,000 make up half of all donations to parties.

I’ve been looking at donations to New Zealand political parties in recent years, for a variety of reasons.

Party funding is one of the perennial topics of politics, mostly because of one pretty fundamental concern, which is that donations can buy influence and access. Modern political parties cost a lot of money to run, and rely heavily on private donations, so it seems highly likely that parties will be very sensitive to the needs of people who give them money.

And if certain people are more able than others to give to parties, as is the case in a New Zealand where inequality of income is much greater than it was 30 years ago, then it is highly likely they will have more influence over politics than others, which goes fundamentally against the idea of a democratic society where everyone has an equal voice.

So, I’ve taken the Electoral Commission’s annual summaries of party donations, which the parties have to declare (as total amounts) in bands of $1500-5000 and $5000-15,000, and (as total amounts, and with the names of donors) $15,000 and over. I’ve looked at donations for 2011-16 because that covers two electoral cycles (two election years and four non-election years) and because the data for earlier years is harder to work with.

The results are in the table below. As you can see, National dominates the fundraising stakes, while donations over $15,000 make up half of all donations to parties. The latter point raises concerns that the parties are, if not reliant on individual wealthy donors, certainly reliant on wealthy donors as a class.

It is technically possible that many of the donations over $15,000 come not from the wealthy but from organisations such as trade unions. I’ll be going through the parties’ returns of donations in more detail shortly to check out that hypothesis, but we know already from the declarations of donations over $30,000 that very few of them come from unions, so it would be surprising if the hypothesis were true.

It’s also possible that the Green Party’s large number of donations over $15,000 is influenced by tithing (paying a percentage of their salary) by their MPs. Again, a closer look will confirm that.

As a final technical note, in 2012 my calculations of the party donations don’t match those of the Electoral Commission for three parties: ACT, Democrats Social Credit, and the Green Party. I’ll check that divergence with the commission, but in any case, it isn’t enough to materially affect the results.

For those deeply interested, the donations summaries from the Commission, and my workings, are in the spreadsheet below.

Is there much wealth mobility in New Zealand?

While many people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives, a very large number of people remain poor for a very long time.

There has been lots of coverage yesterday and today of my latest wealth inequality research (carried out with my father and Wilma Molano from Statistics New Zealand), most of it focusing on our findings about the very limited amount of assets that the average person owns.

However, we also looked at mobility – that is, whether people move up and down the wealth spectrum over time, whether they go from being poor to wealthy, or vice versa.

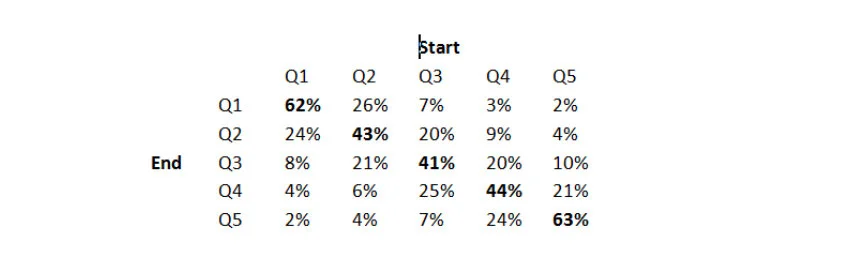

Below is a table which is slightly difficult to interpret for the lay person, but which shows what happens to people in the different quintiles (that is, fifths of the population) over the six years of survey data that we analysed.

Source: Rashbrooke, Rashbrooke and Molano, ‘Wealth Disparities in New Zealand: Final Report’ (http://igps.victoria.ac.nz/publications/files/5327cc2a82f.pdf).

Q1 represents the poorest fifth of the population, Q5 the wealthiest. Each column takes one fifth of the population and shows which group they ended up in after six years. For instance, of those who started in the poorest fifth (the Q1 column), 24% ended in the next group up, while just 2% ended up in the wealthiest group.

The figures in bold are the percentage of each group who stayed in the same position across six years. As you can see, over that period, over 60% of people in the poorest and richest groups stayed where they were, but just over 40% for the middle groups. That’s not surprising: you’d expect it to be relatively easy to move up and down the middle class groups, but for rich and poor to be more fixed.

The data show a ‘diminishing decay’ – people continue to move up and down as the years go on, but once those most likely to move have done so, only a few more extra each year change position. Predicting that trend forward 20 years (using some maths described in the paper), we suggested that around 55% of the wealthy and poor people surveyed would not move over two decades, and 35% of the three central groups would also not move.

What does one make of this? Both glass half empty and glass half full responses are possible. One could say that this shows that very large numbers of people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives.

However, one could also say that it shows very large numbers of people remaining poor for very long periods. Personally, I focus on the latter response: while it is important to recognise what works well, the greatest effort has to go into dealing with the things that aren’t working well, and the significant entrenched poverty suggested by these findings is to me quite troubling.

The UBI vs state jobs

Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems, but let’s not forget about people’s ability to create meaning in their lives.

The Financial Times has an interesting piece by Manchester University’s Diane Coyle critiquing the UBI.

She makes two points, both based around communal ideas. The first is that people don’t just need income, they need jobs, because going to work is important for one’s identity and levels of social contact; the guarantee of a job is part of the social contract. The second is that one can’t just give people income and leave them to sink or swim; they also need strong, free public services that are universally available.

“…it is not surprising the idea of UBI has been revived. But it is hard to see why it would do better at addressing the economic and social costs of large-scale redundancy than the previous policy of making payments to those who lost their jobs. The problem is a hole torn in the fabric of a local or regional economy and society; giving people money is a temporary patch. Part of the answer must be the simpler one of giving people jobs … [Also] more important that UBI — whose focus is the individual — is a commitment to universal basic service, with a focus on the community or the natural economic region.”

In my view, the second point has some weight. Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems; that’s why governments have for a long time provided not just welfare payments but also health, education and other services. And one of the problems for the UBI – which I’m generally skeptical about – is that it creates a large extra cost on top of other government spending.

I’m not so sure about the first point, though. It seems to put paid work on a pedestal, even though much unpaid work – such as child-rearing – is surely as valuable as, or more valuable than, a lot of the jobs that people do. I’d have thought the answer was to redefine what counts as work; then people would be free to work on voluntary activities and the like without the stigma of being ‘unemployed’.

I also think the argument ignores people’s ability to create meaning in their lives. Yes, community and connection with others is important. But if people received a UBI – or some other form of more generous welfare payment – they would presumably be free to create their own communities, their own meaningful connections with others, in a more natural and successful way than if they were allocated jobs by any government, no matter how well-meaning.

In short, I think there are other good reasons to be skeptical about the UBI – but this probably isn’t one of them.

Data shows dramatic decline in Key’s popularity

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician. Not so, it turns out.

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician, someone without parallel in modern history, an unmatchable asset for the National Party while he was its leader.

Not so, it turns out. Data from polling firm UMR, which has been referred to previously but not as far as I know published, shows that Key was no more popular than his predecessor, Helen Clark, and that his popularity took a massive dive over the last year of his reign – which may help explain his resignation in December.

The claims about Key’s success rest on his ‘preferred prime minister’ rating, which did indeed remain stratospheric. But the preferred prime minister ranking was relative: it asked people how much they liked Key compared to the alternatives. Because no one was ever very excited about the alternatives (Phil Goff, David Shearer, David Cunliffe and Andrew Little), Key’s ranking looked good.

But UMR has for years now asked a different, more straightforward question: do you have a favourable or unfavourable view of the prime minister? This is equivalent to the much-discussed favourability ratings for American presidents. And it’s hard to argue with these numbers, which are derived from a simple, relatively objective question (people are asked if their opinion of a politician is very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable, with the results condensed into two categories) that has been asked consistently over a couple of decades.

The results, in the graph above, are striking. The dark red line at the top is Clark’s favourability rating; the dark blue line is Key’s. (The lighter coloured lines at the bottom are the natural inverses, their unfavourability ratings.)

What it shows is that, throughout their reigns, Clark often had a better favourability rating than Key – even in her last term when, according to received wisdom, everyone had fallen out of love with her. So the idea that Key was a politician without precedent simply doesn’t hold. What’s also striking is how much Key’s rating declined, not just from his first-term high but even after the 2014 election.

So what does this tell us? Probably that, for better or worse, personal attacks do work: Labour’s criticisms of Key’s behaviour eroded his popularity, just as National’s did for Clark.

Also that no one is untouchable or immune from that apparently basic law that the public always gets bored of you. The declines in Key’s popularity look to be linked to specific, well-known issues, such as the ponytail-pulling, the flag debate and the TPPA, so the things that some commentators thought should have dented his popularity in fact probably did, even if it wasn’t obvious from the preferred prime minister ranking.

These data may also help explain Key’s sudden resignation. He is on record as saying that, compared to successful traders, most people are too slow to sell failing stock. Given how much National invest in polling, I imagine Key knew something similar to these results, and may have concluded that he should get out now before things got worse. (The final jump in his rating is a post-resignation one; people like it when you go on your own terms and with dignity.) It’s hard to be certain, of course – but that seems like a more convincing explanation than some of the theories that have been circulating ever since he stepped down.