The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Newsroom: A big idea 1 — Crowdsource our laws

Why should we wait around for Parliament, when we have good ideas of our own?

Read the original article on Newsroom

Max Rashbrooke is a research associate at Victoria University of Wellington’s Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, and has just published the report Bridges Both Ways: Transforming the openness of New Zealand government. This article sets out the first of five ‘big ideas’ drawn from the report, with the rest to follow in subsequent weeks.

Number One: Crowdsourced bills

For most people, the process by which laws are made is a hopelessly arcane one. They have no idea how they might ever get involved in proposing or writing something that might one day become law. The procedures of Parliament are a complete mystery to them.

Of course, you could say that that’s what we have MPs for, and that’s true, up to a point. But they hardly have a monopoly on ideas for good laws, and there’s no guarantee they will think of everything that people might want put forward.

Fortunately, other countries have been thinking of ways to demystify the lawmaking process. Indeed some of the most exciting democratic innovations around the world involve the public in directly crafting and proposing legislation. One that’s worth looking at closely is Finland’s creation, around five years ago, of an online platform where citizens can propose laws that its parliament must vote on if they attract more than 50,000 signatures.

New Zealand could follow this lead by creating a secure online platform for people to put up their ideas for draft bills. That could be a bill for a ‘Google tax’ like the one Australia has, or to create incentives for local councils to free up land for housing, or to decriminalise abortion. Whatever people proposed, the form they’d fill out would require them to give reasons for their bill, cite evidence and carefully explain how it would achieve what they wanted. That would do a lot to deter trivial or poorly-considered proposals.

Why should we wait around for Parliament, when we have good ideas of our own?

A small number of the proposed bills would be selected each year to go before Parliament, via some kind of democratic process. It could be that, as in Finland, all those with the support of more than 1 percent of eligible voters – which in New Zealand would be around 35,000 people – could go forward, or Parliament could reserve a few places each year for the top-voted crowdsourced bills, as it does for the Members’ Bills put up by opposition and backbench MPs. And Parliament would have to give priority to crowdsourced bills, to ensure they don’t get put off forever while the Government gets its own bills through.

As with Members’ Bills, the selected bills would be passed onto the Office of the Clerk to be drafted and improved, as another quality check and to increase the chance of their being passed. And they would, if supported by MPs, go through the normal process of being examined by select committees and commented on in public consultation. There is, admittedly, no guarantee the bills would become law. But Finland has shown it can work – the bill that gave them marriage equality was a crowdsourced one. And what’s certain is that the process would force politicians to give the bills a fair hearing, and would raise the stakes for going against popular sentiment. Even when crowdsourced bills don’t succeed, they create valuable debate and lay the groundwork for later change.

Official drafting and Parliamentary sovereignty would play an important role in checking poorly-considered or illiberal measures. If, for instance, someone suggested bringing back the death penalty, or a law that would trample on the rights of minorities, Parliament would still be there to stop it going through. In any case, the Finnish experience shows people use the process to suggest pretty reasonable (though of course debatable) things, like tougher penalties for drunk driving and changes to copyright laws.

If implemented, this process could provide a more concrete target for petitions, which currently get handed to a select committee and then, usually, die a quiet death. Crowdsourced bills would largely do away with the need for citizens-initiated referenda, except where individuals wanted to show overwhelming public support for their proposal. But if they still went down that route, successful referenda could likewise generate a draft bill to go before Parliament. The crowdsourcing process could also work in tandem with methods where government departments create radically open places to debate or ‘crowdsource’ legislation, while retaining control of the progress of laws.

The Finnish experience shows these things can work. And, what’s more, they help people feel like they can ‘do’ politics. Research shows that the crowdsourced bill process can engage people who aren’t otherwise politically active, including those in marginalised groups. In short, it’s an easy way to demystify a complex process, and to bring the art of law-making within everyone’s grasp. MPs will always run most of Parliament’s business – but why should we always wait around for them, when we have good ideas of our own?

Why a referendum on smacking is a terrible idea

How does democracy protect the interests of those who don’t get a vote?

New Zealand First has just announced that it wants a referendum – another one, but binding this time – on our anti-smacking laws.

I’m not opposed to binding referenda in principle, although I do think they are the bluntest tool in the direct democracy toolbox, so you might think that I’d support this call.

I don’t, though, for several reasons. For a start, it’s been relatively recently debated, and settled, and there is no evidence for a need to revisit the issue. The police are not going around arresting thousands of people inappropriately or prosecuting parents for the kinds of force that are permitted under the act.

There is also the very strong evidence that physical punishment of children doesn’t work, and in fact is counter-productive, being liable to increase their levels of aggression later in life.

Most fundamentally, though, a referendum of this kind would strongly raise the question of who gets to vote. Most major issues predominantly affect adults, so it’s not really a problem that only adults vote. This issue, however, has huge consequences for children, yet they get no say in it. Even though there are extremely obvious, and generally unproblematic, reasons why children don’t get to vote, issues like this do raise a wider question. Namely, how does democracy protect the interests of those who don’t get a vote?

The same point applies, in a sense, to the environment, which obviously can’t ‘represent’ itself in a democratic process, and to future generations, who will be powerfully affected by our decisions now, and yet cannot influence them.

What society does in these situations, increasingly, is create bodies that can represent those groups. The Children’s Commissioner and the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment exist at least in part to create a ‘vote’ or ‘voice’ for otherwise excluded parties. In contrast, a referendum would do nothing to enhance the voice of children.

Referenda can also be dangerous because of the well-known potential for the majority to interfere with the liberties of the minority. In a country with strong constitutional protections for minorities, those dangers are minimised, but New Zealand does not have those protections. Again, there is great potential for the rights and interests of children, a very important minority, to be overridden in ways that are highly problematic.

In short, although an appeal to let ‘the people’ decide always sounds appealing, it is not always the right option, and certainly isn’t in this case.

Donations to political parties 2011-16

National dominates the fundraising stakes, while donations over $15,000 make up half of all donations to parties.

I’ve been looking at donations to New Zealand political parties in recent years, for a variety of reasons.

Party funding is one of the perennial topics of politics, mostly because of one pretty fundamental concern, which is that donations can buy influence and access. Modern political parties cost a lot of money to run, and rely heavily on private donations, so it seems highly likely that parties will be very sensitive to the needs of people who give them money.

And if certain people are more able than others to give to parties, as is the case in a New Zealand where inequality of income is much greater than it was 30 years ago, then it is highly likely they will have more influence over politics than others, which goes fundamentally against the idea of a democratic society where everyone has an equal voice.

So, I’ve taken the Electoral Commission’s annual summaries of party donations, which the parties have to declare (as total amounts) in bands of $1500-5000 and $5000-15,000, and (as total amounts, and with the names of donors) $15,000 and over. I’ve looked at donations for 2011-16 because that covers two electoral cycles (two election years and four non-election years) and because the data for earlier years is harder to work with.

The results are in the table below. As you can see, National dominates the fundraising stakes, while donations over $15,000 make up half of all donations to parties. The latter point raises concerns that the parties are, if not reliant on individual wealthy donors, certainly reliant on wealthy donors as a class.

It is technically possible that many of the donations over $15,000 come not from the wealthy but from organisations such as trade unions. I’ll be going through the parties’ returns of donations in more detail shortly to check out that hypothesis, but we know already from the declarations of donations over $30,000 that very few of them come from unions, so it would be surprising if the hypothesis were true.

It’s also possible that the Green Party’s large number of donations over $15,000 is influenced by tithing (paying a percentage of their salary) by their MPs. Again, a closer look will confirm that.

As a final technical note, in 2012 my calculations of the party donations don’t match those of the Electoral Commission for three parties: ACT, Democrats Social Credit, and the Green Party. I’ll check that divergence with the commission, but in any case, it isn’t enough to materially affect the results.

For those deeply interested, the donations summaries from the Commission, and my workings, are in the spreadsheet below.

Is there much wealth mobility in New Zealand?

While many people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives, a very large number of people remain poor for a very long time.

There has been lots of coverage yesterday and today of my latest wealth inequality research (carried out with my father and Wilma Molano from Statistics New Zealand), most of it focusing on our findings about the very limited amount of assets that the average person owns.

However, we also looked at mobility – that is, whether people move up and down the wealth spectrum over time, whether they go from being poor to wealthy, or vice versa.

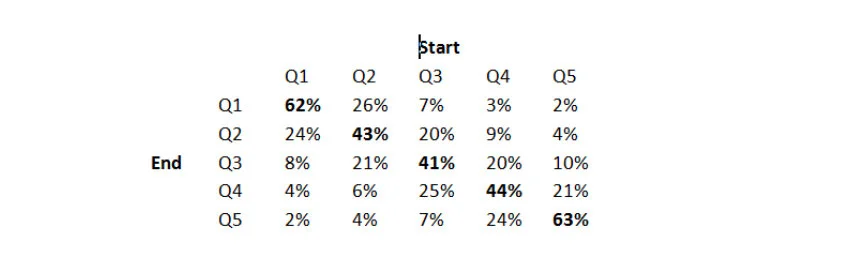

Below is a table which is slightly difficult to interpret for the lay person, but which shows what happens to people in the different quintiles (that is, fifths of the population) over the six years of survey data that we analysed.

Source: Rashbrooke, Rashbrooke and Molano, ‘Wealth Disparities in New Zealand: Final Report’ (http://igps.victoria.ac.nz/publications/files/5327cc2a82f.pdf).

Q1 represents the poorest fifth of the population, Q5 the wealthiest. Each column takes one fifth of the population and shows which group they ended up in after six years. For instance, of those who started in the poorest fifth (the Q1 column), 24% ended in the next group up, while just 2% ended up in the wealthiest group.

The figures in bold are the percentage of each group who stayed in the same position across six years. As you can see, over that period, over 60% of people in the poorest and richest groups stayed where they were, but just over 40% for the middle groups. That’s not surprising: you’d expect it to be relatively easy to move up and down the middle class groups, but for rich and poor to be more fixed.

The data show a ‘diminishing decay’ – people continue to move up and down as the years go on, but once those most likely to move have done so, only a few more extra each year change position. Predicting that trend forward 20 years (using some maths described in the paper), we suggested that around 55% of the wealthy and poor people surveyed would not move over two decades, and 35% of the three central groups would also not move.

What does one make of this? Both glass half empty and glass half full responses are possible. One could say that this shows that very large numbers of people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives.

However, one could also say that it shows very large numbers of people remaining poor for very long periods. Personally, I focus on the latter response: while it is important to recognise what works well, the greatest effort has to go into dealing with the things that aren’t working well, and the significant entrenched poverty suggested by these findings is to me quite troubling.

The UBI vs state jobs

Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems, but let’s not forget about people’s ability to create meaning in their lives.

The Financial Times has an interesting piece by Manchester University’s Diane Coyle critiquing the UBI.

She makes two points, both based around communal ideas. The first is that people don’t just need income, they need jobs, because going to work is important for one’s identity and levels of social contact; the guarantee of a job is part of the social contract. The second is that one can’t just give people income and leave them to sink or swim; they also need strong, free public services that are universally available.

“…it is not surprising the idea of UBI has been revived. But it is hard to see why it would do better at addressing the economic and social costs of large-scale redundancy than the previous policy of making payments to those who lost their jobs. The problem is a hole torn in the fabric of a local or regional economy and society; giving people money is a temporary patch. Part of the answer must be the simpler one of giving people jobs … [Also] more important that UBI — whose focus is the individual — is a commitment to universal basic service, with a focus on the community or the natural economic region.”

In my view, the second point has some weight. Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems; that’s why governments have for a long time provided not just welfare payments but also health, education and other services. And one of the problems for the UBI – which I’m generally skeptical about – is that it creates a large extra cost on top of other government spending.

I’m not so sure about the first point, though. It seems to put paid work on a pedestal, even though much unpaid work – such as child-rearing – is surely as valuable as, or more valuable than, a lot of the jobs that people do. I’d have thought the answer was to redefine what counts as work; then people would be free to work on voluntary activities and the like without the stigma of being ‘unemployed’.

I also think the argument ignores people’s ability to create meaning in their lives. Yes, community and connection with others is important. But if people received a UBI – or some other form of more generous welfare payment – they would presumably be free to create their own communities, their own meaningful connections with others, in a more natural and successful way than if they were allocated jobs by any government, no matter how well-meaning.

In short, I think there are other good reasons to be skeptical about the UBI – but this probably isn’t one of them.

Data shows dramatic decline in Key’s popularity

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician. Not so, it turns out.

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician, someone without parallel in modern history, an unmatchable asset for the National Party while he was its leader.

Not so, it turns out. Data from polling firm UMR, which has been referred to previously but not as far as I know published, shows that Key was no more popular than his predecessor, Helen Clark, and that his popularity took a massive dive over the last year of his reign – which may help explain his resignation in December.

The claims about Key’s success rest on his ‘preferred prime minister’ rating, which did indeed remain stratospheric. But the preferred prime minister ranking was relative: it asked people how much they liked Key compared to the alternatives. Because no one was ever very excited about the alternatives (Phil Goff, David Shearer, David Cunliffe and Andrew Little), Key’s ranking looked good.

But UMR has for years now asked a different, more straightforward question: do you have a favourable or unfavourable view of the prime minister? This is equivalent to the much-discussed favourability ratings for American presidents. And it’s hard to argue with these numbers, which are derived from a simple, relatively objective question (people are asked if their opinion of a politician is very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable, with the results condensed into two categories) that has been asked consistently over a couple of decades.

The results, in the graph above, are striking. The dark red line at the top is Clark’s favourability rating; the dark blue line is Key’s. (The lighter coloured lines at the bottom are the natural inverses, their unfavourability ratings.)

What it shows is that, throughout their reigns, Clark often had a better favourability rating than Key – even in her last term when, according to received wisdom, everyone had fallen out of love with her. So the idea that Key was a politician without precedent simply doesn’t hold. What’s also striking is how much Key’s rating declined, not just from his first-term high but even after the 2014 election.

So what does this tell us? Probably that, for better or worse, personal attacks do work: Labour’s criticisms of Key’s behaviour eroded his popularity, just as National’s did for Clark.

Also that no one is untouchable or immune from that apparently basic law that the public always gets bored of you. The declines in Key’s popularity look to be linked to specific, well-known issues, such as the ponytail-pulling, the flag debate and the TPPA, so the things that some commentators thought should have dented his popularity in fact probably did, even if it wasn’t obvious from the preferred prime minister ranking.

These data may also help explain Key’s sudden resignation. He is on record as saying that, compared to successful traders, most people are too slow to sell failing stock. Given how much National invest in polling, I imagine Key knew something similar to these results, and may have concluded that he should get out now before things got worse. (The final jump in his rating is a post-resignation one; people like it when you go on your own terms and with dignity.) It’s hard to be certain, of course – but that seems like a more convincing explanation than some of the theories that have been circulating ever since he stepped down.

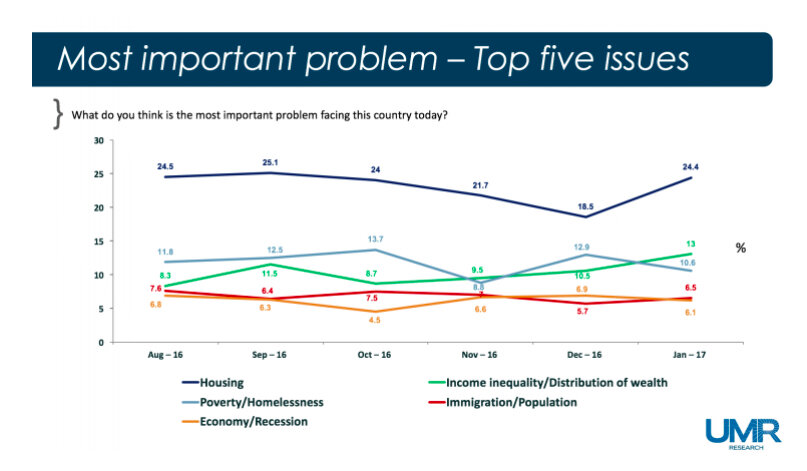

Polling: housing vs poverty vs inequality

When you ask people what they think the most important problem facing the country is, about as many people say ‘housing’ as ‘poverty’ and ‘inequality’ combined.

Previous polling data about what’s on the public’s mind has often run together poverty and inequality, and sometimes even conflated them with housing.

So what happens when you split the three issues up, as polling firm UMR has helpfully done for the last six months and summarised below? Well, when you ask people what they think is the most important problem facing the country, about as many people say ‘housing’ as ‘poverty’ and ‘inequality’ together.

That’s no great surprise, since people in middle New Zealand don’t necessarily see poverty and inequality as affecting them directly, while the housing crisis obviously does.

It’s interesting, though, to see that income and wealth inequality is just as important to people as poverty. Various commentators would argue (or like to argue) that people only care about poverty (that is, whether some are struggling) and not about inequality (the fact that some people are richer than others). In fact, that’s not the case, which is probably because people have strong intuitions about what is just or fair when it comes to the distribution of rewards.

In any case, both poverty and the housing crisis are ultimately symptoms of inequality. People are so poor in part because, in an unequal society, there is so little of the pie left over for them to claim. And housing shortages are a phenomenon that disproportionately affects people who are poor, as well as those in the middle. After all, there’s no housing shortage from a millionaire’s point of view.

People haven’t necessarily made the full connection between these three issues, though, so I suppose that one of the questions for the 2017 election is to what extent those dots will be joined and, if they are, what effect will it have on the contest.

TOP’s Democracy Reset: good principles, rushed execution

Some good ideas, but they won’t solve the fundamental problems of our democracy.

Gareth’s Morgan’s The Opportunities Party (TOP) yesterday announced its ‘Democracy Reset’, tapping into the growing public sense that democracy isn’t working the way it should. And it’s right to identify concentrated power within Cabinet, falling voter turnout and vested interests as key threats to the system. But while it has some good ideas, it doesn’t offer either a radical or a coherent way to really hand back power to the people.

The problems start when it accepts uncritically some research from last year claiming to show that millennials don’t care about democracy – research that has been very strongly questioned (on the grounds that we don’t know what millennials will think about democracy when they reach the age that people born in the 1930s are now).

The TOP policy also concentrates oddly on two quite technocratic and not obviously essential fixes. The first is restoring an Upper House, which is supposed to take power from the executive and restore it to Parliament.

But the Upper House would almost certainly be advisory, so it could in fact be ignored, just like the current attorney-general’s warnings about human rights violations are ignored. Whereas if it did have some decisive power, all sorts of questions about the legitimacy of an Upper House would be raised, especially if some of its member were appointed, not elected. These complex questions don’t seem to have been considered.

Also, if we want more expert scrutiny of bills, which seems to be the point, why don’t we work that into the current system, for instance by strengthening the select committee process? There are good examples from other countries where that happens. So an Upper House doesn’t seem very necessary to achieve the stated goals.

The next section, ‘Empowerment of People’, is broadly sensible: devolution of power, deliberative democracy, and civics. But it doesn’t say anything definitive that really counts. Saying “let’s have devolution” is easy; what matters is which powers are devolved, and how you resolve the tricky issue of maintaining central oversight and expertise while giving locals control.

Similarly, I couldn’t be more pleased to hear a party call for “collaborative software, participatory budgeting and citizen’s juries/assemblies”, but how will they be used? And how would TOP deal with the classic problems, such as the questions over the status of the results of such things (whether they really represent the public) and the fact they are normally ignored by parliaments?

Then, the section on the second technocratic solution, a written Constitution, is pretty slapdash. Key rights from the Indian constitution are posted in full, suggesting we need to consider “the abolition of untouchability” (!), but there’s no discussion of crucial things for a New Zealand constitution: property rights; economic, social and cultural rights (and whether they are something that should be in a constitution); etc.

Bizarrely, there is no mention of whether this constitution would be enforceable by the courts, in the sense that judges could, as in the US, strike down laws they deem inconsistent with it – even though this is one of the key questions about any written constitution. Also, if the courts could do that, it would be the precise opposite of TOP’s stated aim of restoring sovereignty to Parliament!

Elsewhere, TOP advocates for strengthening the position of the Treaty, which seems very welcome, though I’m not qualified to comment on whether its proposals go far enough.

Finally, there is a very cursory section on media and the public sector, which consists solely of a plan to sell TVNZ to fund journalism on other platforms (potentially sensible but surely not the whole solution to media problems), and a call for “more open and transparent government”, which again is sensible but totally free of details, especially on crucial questions such as how to restore the provision of free and frank advice in a world where ministers often don’t want to hear it.

In short, while I don’t disagree with much of the above, it all feels very rushed and piecemeal, most of the key questions are ducked, and the fundamental problems of our democracy – disengagement and the lack of genuine decision-making power for most citizens – aren’t going to be changed by such policies.

A modest proposal to aid voting on DHB elections

Let’s make the process easier with DHB statements and clear, standardised information about candidates.

Local Government New Zealand’s Mike Reid has an interesting piece in the latest Policy Quarterly about local council turnout. (Short version: it’s low largely because councils don’t have many powers, and this is set to get worse as central government reforms strip even more power from them.)

One of the other factors behind low turnout, Reid argues, is that people have to elect not just councillors but also district health board members, and the complexity of the latter is highly off-putting.

Assuming this is true, I don’t think the answer is – as Mike Hosking has argued, if that’s the right word – to give up on electing DHBs. It’s important to have citizens’ voices shaping policy; the Capital Coast DHB recently paid tribute to the work of one elected member, David Choat, for distinctly improving the quality of their decisions.

So how to make it easier to elect people to DHBs? I suspect the first problem is that people simply don’t know what DHBs are and what they do. I can’t recall exactly how much information about DHBs was provided in this year’s election booklet, but I don’t think it was very extensive or done very well.

One step might be to have a clear statement of what each DHB does – both in print and online – including perhaps a plain English statement of the five key things each DHB has identified it wants to deal with in the coming years.

More than that, though, I think most people struggle to work out who to vote for, given there are generally no party affiliations to rely on, the published bios can be pretty vague, and most people are legitimately a bit busy to go hunting for further information that may not exist. Groups like the Public Health Association (PHA) do good rankings of candidates, but most people don’t see them.

My solution – coming from a journalistic background – would be to require each candidate to answer (say) five basic questions about what they would do on key policy issues facing the DHB. That’d provide nice, clear, standardised information to help voters work out if they agree with candidates. (Any candidate providing daft or minimal answers would hopefully get ignored by voters.) If candidates had to provide their stance on fluoridation, for instance (as the PHA asks them to do), you would quickly know which ones were – to put it politely – out of touch with scientific reality.

The problem would be how to pick the questions. But the Electoral Commission could survey voters in advance to find out what questions they most want answered, and then augment that with feedback from a panel of health experts. The end result would be an objectively important set of questions – and a much easier choice for voters.

On Gareth Morgan’s ‘new’ tax, and the UBI gone

Sticking to the current tax take isn’t a radical or evidence-based position: it’s a cautious, centrist one.

Gareth Morgan’s The Opportunities Party yesterday (re)announced its first policy, Morgan’s long-standing plan for a comprehensive capital income tax. In effect, the policy argues that all forms of wealth generate – or should generate – income, just like savings accumulate interest, and that this income should be taxed, just like interest is.

Most controversially, the policy argues that people’s houses effectively generate an income, in the form of the money they save by not having to pay rent. Thus, housing should be taxed.

I broadly support the policy, because it increases equality by taxing all forms of income, not just those currently covered, and because it brings into the tax system large numbers of people who are currently probably paying very little tax. It would probably also lead to wealth being better used.

Personally, I would make the tax progressive, so that people with more wealth paid a large percentage, as Thomas Piketty advocates, because this would act even more strongly against inequality, and because (as Piketty shows) larger fortunes generate larger returns.

I also wonder about whether we want to treat people’s houses this way. Of course houses are technically assets; indeed owner-occupied housing is probably around 40% of all household wealth. But houses are, much more importantly, places to live – places where people nurture their dreams and bring up their families, places steeped in memories and stories. In the modern world too many things are already valued in monetary terms. Do we really want to further emphasise the financial aspect of that most important part of human life, the house?

On those grounds, I would think about exempting owner-occupied housing, although this would take a huge amount of wealth out of the tax net, or least exempting the value of the house above a certain level – say, the average house price – so as to try to separate out the basic shelter element (which, as above, should perhaps not be taxed) – from the investment element, which should.

UBI gone – for now

Almost more significant than the tax announcement, however, was Morgan’s admission that he would not be arguing for a universal basic income, at least for now.

It’s not absolutely clear why – except that Morgan obviously feels it’s not politically viable. When I asked him about it on Twitter, he said: “UBI can’t be funded until we have integrity in tax base. Our work on a modest UBI & funding says fix the hole first.”

But the capital income tax doesn’t “fix the hole” in New Zealand’s tax system, because the policy explicitly says that any money it raises will be offset by income tax cuts.

Morgan also said: “Financing that [the UBI] is a real challenge. There’s a way but it would be a step too far at this time.” I’m not sure what that “way” is. But at any rate, the UBI won’t be part of “phase 1” of TOP, however long that lasts.

I think this is significant because it contradicts Morgan’s two claims on launching TOP: that it would radically shake up a middle-of-the-road political establishment, and that it would be evidence-based.

The UBI is one of Morgan’s signature policies, and one of his most radical. (I have reservations about it, but that’s beside the point here.) To drop it, or least put it in the deep freezer, because it would be “a step too far” is exactly the kind of realpolitik-style, unadventurous incrementalism that he has attacked in the existing parties.

The UBI is also, for Morgan at least, evidence-based: he has spent a lot of time arguing that the evidence shows how well it would work. Again, putting it off seems difficult to justify, given his stated aims.

Morgan would, with some justification, probably argue that the capital income tax is quite radical enough already, for the average New Zealander at least. But I’m not sure you can have it both ways, that you can claim that you are going to “light a fuse” under parliament, then back away from one of your signature radical steps because you’re not sure it’s politically achievable.

As a final note, part of the reason the UBI is currently out of bounds for Morgan is that he seems determined to maintain New Zealand’s tax take at its current level, albeit switching some wealth and income taxes. But it’s hard to see why he takes that stance. New Zealand has one of the lowest tax takes in the world, and there’s a very strong (and evidence-based!) argument that we need a bigger tax take to bolster struggling public services (such as health, which has had inflation-adjusted funding cuts of $1.7 billion in the last few years) and improve our economic and social infrastructure.

Sticking to the current tax take isn’t a radical or evidence-based position: it’s a cautious, centrist one. And unless you think that opportunities can be generated for free, or there is currently massive waste in New Zealand public spending, I’m not sure where Morgan will find the money to pay for the other opportunity-generating policies he is presumably going to launch.

So, in short, while I support quite a lot of the policies that Morgan advocates, I’m not sure that his party is going to be able to achieve what he wants it to.