The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Is there much wealth mobility in New Zealand?

While many people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives, a very large number of people remain poor for a very long time.

There has been lots of coverage yesterday and today of my latest wealth inequality research (carried out with my father and Wilma Molano from Statistics New Zealand), most of it focusing on our findings about the very limited amount of assets that the average person owns.

However, we also looked at mobility – that is, whether people move up and down the wealth spectrum over time, whether they go from being poor to wealthy, or vice versa.

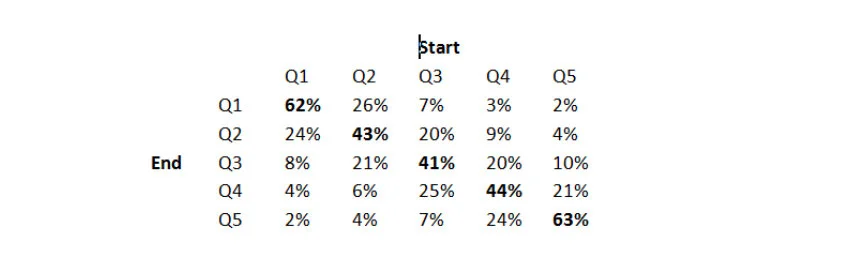

Below is a table which is slightly difficult to interpret for the lay person, but which shows what happens to people in the different quintiles (that is, fifths of the population) over the six years of survey data that we analysed.

Source: Rashbrooke, Rashbrooke and Molano, ‘Wealth Disparities in New Zealand: Final Report’ (http://igps.victoria.ac.nz/publications/files/5327cc2a82f.pdf).

Q1 represents the poorest fifth of the population, Q5 the wealthiest. Each column takes one fifth of the population and shows which group they ended up in after six years. For instance, of those who started in the poorest fifth (the Q1 column), 24% ended in the next group up, while just 2% ended up in the wealthiest group.

The figures in bold are the percentage of each group who stayed in the same position across six years. As you can see, over that period, over 60% of people in the poorest and richest groups stayed where they were, but just over 40% for the middle groups. That’s not surprising: you’d expect it to be relatively easy to move up and down the middle class groups, but for rich and poor to be more fixed.

The data show a ‘diminishing decay’ – people continue to move up and down as the years go on, but once those most likely to move have done so, only a few more extra each year change position. Predicting that trend forward 20 years (using some maths described in the paper), we suggested that around 55% of the wealthy and poor people surveyed would not move over two decades, and 35% of the three central groups would also not move.

What does one make of this? Both glass half empty and glass half full responses are possible. One could say that this shows that very large numbers of people who are poor at one stage go on to become wealthier over their lives.

However, one could also say that it shows very large numbers of people remaining poor for very long periods. Personally, I focus on the latter response: while it is important to recognise what works well, the greatest effort has to go into dealing with the things that aren’t working well, and the significant entrenched poverty suggested by these findings is to me quite troubling.

The UBI vs state jobs

Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems, but let’s not forget about people’s ability to create meaning in their lives.

The Financial Times has an interesting piece by Manchester University’s Diane Coyle critiquing the UBI.

She makes two points, both based around communal ideas. The first is that people don’t just need income, they need jobs, because going to work is important for one’s identity and levels of social contact; the guarantee of a job is part of the social contract. The second is that one can’t just give people income and leave them to sink or swim; they also need strong, free public services that are universally available.

“…it is not surprising the idea of UBI has been revived. But it is hard to see why it would do better at addressing the economic and social costs of large-scale redundancy than the previous policy of making payments to those who lost their jobs. The problem is a hole torn in the fabric of a local or regional economy and society; giving people money is a temporary patch. Part of the answer must be the simpler one of giving people jobs … [Also] more important that UBI — whose focus is the individual — is a commitment to universal basic service, with a focus on the community or the natural economic region.”

In my view, the second point has some weight. Income alone doesn’t solve all people’s problems; that’s why governments have for a long time provided not just welfare payments but also health, education and other services. And one of the problems for the UBI – which I’m generally skeptical about – is that it creates a large extra cost on top of other government spending.

I’m not so sure about the first point, though. It seems to put paid work on a pedestal, even though much unpaid work – such as child-rearing – is surely as valuable as, or more valuable than, a lot of the jobs that people do. I’d have thought the answer was to redefine what counts as work; then people would be free to work on voluntary activities and the like without the stigma of being ‘unemployed’.

I also think the argument ignores people’s ability to create meaning in their lives. Yes, community and connection with others is important. But if people received a UBI – or some other form of more generous welfare payment – they would presumably be free to create their own communities, their own meaningful connections with others, in a more natural and successful way than if they were allocated jobs by any government, no matter how well-meaning.

In short, I think there are other good reasons to be skeptical about the UBI – but this probably isn’t one of them.

Data shows dramatic decline in Key’s popularity

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician. Not so, it turns out.

It’s become received political wisdom that John Key was a superhumanly popular politician, someone without parallel in modern history, an unmatchable asset for the National Party while he was its leader.

Not so, it turns out. Data from polling firm UMR, which has been referred to previously but not as far as I know published, shows that Key was no more popular than his predecessor, Helen Clark, and that his popularity took a massive dive over the last year of his reign – which may help explain his resignation in December.

The claims about Key’s success rest on his ‘preferred prime minister’ rating, which did indeed remain stratospheric. But the preferred prime minister ranking was relative: it asked people how much they liked Key compared to the alternatives. Because no one was ever very excited about the alternatives (Phil Goff, David Shearer, David Cunliffe and Andrew Little), Key’s ranking looked good.

But UMR has for years now asked a different, more straightforward question: do you have a favourable or unfavourable view of the prime minister? This is equivalent to the much-discussed favourability ratings for American presidents. And it’s hard to argue with these numbers, which are derived from a simple, relatively objective question (people are asked if their opinion of a politician is very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable, with the results condensed into two categories) that has been asked consistently over a couple of decades.

The results, in the graph above, are striking. The dark red line at the top is Clark’s favourability rating; the dark blue line is Key’s. (The lighter coloured lines at the bottom are the natural inverses, their unfavourability ratings.)

What it shows is that, throughout their reigns, Clark often had a better favourability rating than Key – even in her last term when, according to received wisdom, everyone had fallen out of love with her. So the idea that Key was a politician without precedent simply doesn’t hold. What’s also striking is how much Key’s rating declined, not just from his first-term high but even after the 2014 election.

So what does this tell us? Probably that, for better or worse, personal attacks do work: Labour’s criticisms of Key’s behaviour eroded his popularity, just as National’s did for Clark.

Also that no one is untouchable or immune from that apparently basic law that the public always gets bored of you. The declines in Key’s popularity look to be linked to specific, well-known issues, such as the ponytail-pulling, the flag debate and the TPPA, so the things that some commentators thought should have dented his popularity in fact probably did, even if it wasn’t obvious from the preferred prime minister ranking.

These data may also help explain Key’s sudden resignation. He is on record as saying that, compared to successful traders, most people are too slow to sell failing stock. Given how much National invest in polling, I imagine Key knew something similar to these results, and may have concluded that he should get out now before things got worse. (The final jump in his rating is a post-resignation one; people like it when you go on your own terms and with dignity.) It’s hard to be certain, of course – but that seems like a more convincing explanation than some of the theories that have been circulating ever since he stepped down.

Polling: housing vs poverty vs inequality

When you ask people what they think the most important problem facing the country is, about as many people say ‘housing’ as ‘poverty’ and ‘inequality’ combined.

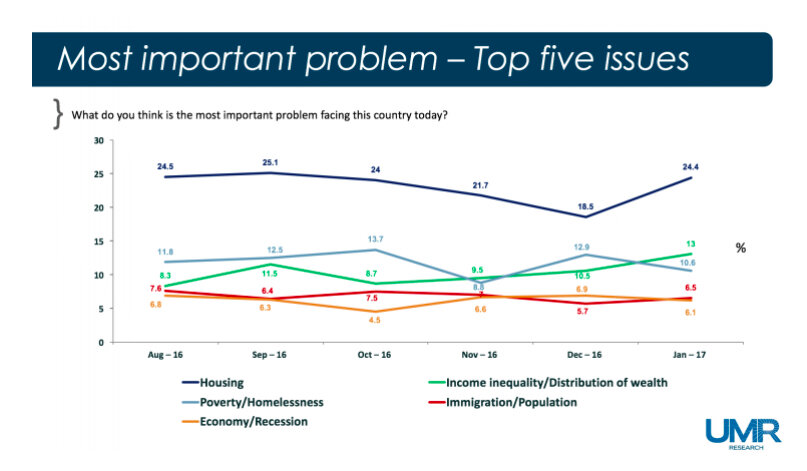

Previous polling data about what’s on the public’s mind has often run together poverty and inequality, and sometimes even conflated them with housing.

So what happens when you split the three issues up, as polling firm UMR has helpfully done for the last six months and summarised below? Well, when you ask people what they think is the most important problem facing the country, about as many people say ‘housing’ as ‘poverty’ and ‘inequality’ together.

That’s no great surprise, since people in middle New Zealand don’t necessarily see poverty and inequality as affecting them directly, while the housing crisis obviously does.

It’s interesting, though, to see that income and wealth inequality is just as important to people as poverty. Various commentators would argue (or like to argue) that people only care about poverty (that is, whether some are struggling) and not about inequality (the fact that some people are richer than others). In fact, that’s not the case, which is probably because people have strong intuitions about what is just or fair when it comes to the distribution of rewards.

In any case, both poverty and the housing crisis are ultimately symptoms of inequality. People are so poor in part because, in an unequal society, there is so little of the pie left over for them to claim. And housing shortages are a phenomenon that disproportionately affects people who are poor, as well as those in the middle. After all, there’s no housing shortage from a millionaire’s point of view.

People haven’t necessarily made the full connection between these three issues, though, so I suppose that one of the questions for the 2017 election is to what extent those dots will be joined and, if they are, what effect will it have on the contest.

TOP’s Democracy Reset: good principles, rushed execution

Some good ideas, but they won’t solve the fundamental problems of our democracy.

Gareth’s Morgan’s The Opportunities Party (TOP) yesterday announced its ‘Democracy Reset’, tapping into the growing public sense that democracy isn’t working the way it should. And it’s right to identify concentrated power within Cabinet, falling voter turnout and vested interests as key threats to the system. But while it has some good ideas, it doesn’t offer either a radical or a coherent way to really hand back power to the people.

The problems start when it accepts uncritically some research from last year claiming to show that millennials don’t care about democracy – research that has been very strongly questioned (on the grounds that we don’t know what millennials will think about democracy when they reach the age that people born in the 1930s are now).

The TOP policy also concentrates oddly on two quite technocratic and not obviously essential fixes. The first is restoring an Upper House, which is supposed to take power from the executive and restore it to Parliament.

But the Upper House would almost certainly be advisory, so it could in fact be ignored, just like the current attorney-general’s warnings about human rights violations are ignored. Whereas if it did have some decisive power, all sorts of questions about the legitimacy of an Upper House would be raised, especially if some of its member were appointed, not elected. These complex questions don’t seem to have been considered.

Also, if we want more expert scrutiny of bills, which seems to be the point, why don’t we work that into the current system, for instance by strengthening the select committee process? There are good examples from other countries where that happens. So an Upper House doesn’t seem very necessary to achieve the stated goals.

The next section, ‘Empowerment of People’, is broadly sensible: devolution of power, deliberative democracy, and civics. But it doesn’t say anything definitive that really counts. Saying “let’s have devolution” is easy; what matters is which powers are devolved, and how you resolve the tricky issue of maintaining central oversight and expertise while giving locals control.

Similarly, I couldn’t be more pleased to hear a party call for “collaborative software, participatory budgeting and citizen’s juries/assemblies”, but how will they be used? And how would TOP deal with the classic problems, such as the questions over the status of the results of such things (whether they really represent the public) and the fact they are normally ignored by parliaments?

Then, the section on the second technocratic solution, a written Constitution, is pretty slapdash. Key rights from the Indian constitution are posted in full, suggesting we need to consider “the abolition of untouchability” (!), but there’s no discussion of crucial things for a New Zealand constitution: property rights; economic, social and cultural rights (and whether they are something that should be in a constitution); etc.

Bizarrely, there is no mention of whether this constitution would be enforceable by the courts, in the sense that judges could, as in the US, strike down laws they deem inconsistent with it – even though this is one of the key questions about any written constitution. Also, if the courts could do that, it would be the precise opposite of TOP’s stated aim of restoring sovereignty to Parliament!

Elsewhere, TOP advocates for strengthening the position of the Treaty, which seems very welcome, though I’m not qualified to comment on whether its proposals go far enough.

Finally, there is a very cursory section on media and the public sector, which consists solely of a plan to sell TVNZ to fund journalism on other platforms (potentially sensible but surely not the whole solution to media problems), and a call for “more open and transparent government”, which again is sensible but totally free of details, especially on crucial questions such as how to restore the provision of free and frank advice in a world where ministers often don’t want to hear it.

In short, while I don’t disagree with much of the above, it all feels very rushed and piecemeal, most of the key questions are ducked, and the fundamental problems of our democracy – disengagement and the lack of genuine decision-making power for most citizens – aren’t going to be changed by such policies.

A modest proposal to aid voting on DHB elections

Let’s make the process easier with DHB statements and clear, standardised information about candidates.

Local Government New Zealand’s Mike Reid has an interesting piece in the latest Policy Quarterly about local council turnout. (Short version: it’s low largely because councils don’t have many powers, and this is set to get worse as central government reforms strip even more power from them.)

One of the other factors behind low turnout, Reid argues, is that people have to elect not just councillors but also district health board members, and the complexity of the latter is highly off-putting.

Assuming this is true, I don’t think the answer is – as Mike Hosking has argued, if that’s the right word – to give up on electing DHBs. It’s important to have citizens’ voices shaping policy; the Capital Coast DHB recently paid tribute to the work of one elected member, David Choat, for distinctly improving the quality of their decisions.

So how to make it easier to elect people to DHBs? I suspect the first problem is that people simply don’t know what DHBs are and what they do. I can’t recall exactly how much information about DHBs was provided in this year’s election booklet, but I don’t think it was very extensive or done very well.

One step might be to have a clear statement of what each DHB does – both in print and online – including perhaps a plain English statement of the five key things each DHB has identified it wants to deal with in the coming years.

More than that, though, I think most people struggle to work out who to vote for, given there are generally no party affiliations to rely on, the published bios can be pretty vague, and most people are legitimately a bit busy to go hunting for further information that may not exist. Groups like the Public Health Association (PHA) do good rankings of candidates, but most people don’t see them.

My solution – coming from a journalistic background – would be to require each candidate to answer (say) five basic questions about what they would do on key policy issues facing the DHB. That’d provide nice, clear, standardised information to help voters work out if they agree with candidates. (Any candidate providing daft or minimal answers would hopefully get ignored by voters.) If candidates had to provide their stance on fluoridation, for instance (as the PHA asks them to do), you would quickly know which ones were – to put it politely – out of touch with scientific reality.

The problem would be how to pick the questions. But the Electoral Commission could survey voters in advance to find out what questions they most want answered, and then augment that with feedback from a panel of health experts. The end result would be an objectively important set of questions – and a much easier choice for voters.

On Gareth Morgan’s ‘new’ tax, and the UBI gone

Sticking to the current tax take isn’t a radical or evidence-based position: it’s a cautious, centrist one.

Gareth Morgan’s The Opportunities Party yesterday (re)announced its first policy, Morgan’s long-standing plan for a comprehensive capital income tax. In effect, the policy argues that all forms of wealth generate – or should generate – income, just like savings accumulate interest, and that this income should be taxed, just like interest is.

Most controversially, the policy argues that people’s houses effectively generate an income, in the form of the money they save by not having to pay rent. Thus, housing should be taxed.

I broadly support the policy, because it increases equality by taxing all forms of income, not just those currently covered, and because it brings into the tax system large numbers of people who are currently probably paying very little tax. It would probably also lead to wealth being better used.

Personally, I would make the tax progressive, so that people with more wealth paid a large percentage, as Thomas Piketty advocates, because this would act even more strongly against inequality, and because (as Piketty shows) larger fortunes generate larger returns.

I also wonder about whether we want to treat people’s houses this way. Of course houses are technically assets; indeed owner-occupied housing is probably around 40% of all household wealth. But houses are, much more importantly, places to live – places where people nurture their dreams and bring up their families, places steeped in memories and stories. In the modern world too many things are already valued in monetary terms. Do we really want to further emphasise the financial aspect of that most important part of human life, the house?

On those grounds, I would think about exempting owner-occupied housing, although this would take a huge amount of wealth out of the tax net, or least exempting the value of the house above a certain level – say, the average house price – so as to try to separate out the basic shelter element (which, as above, should perhaps not be taxed) – from the investment element, which should.

UBI gone – for now

Almost more significant than the tax announcement, however, was Morgan’s admission that he would not be arguing for a universal basic income, at least for now.

It’s not absolutely clear why – except that Morgan obviously feels it’s not politically viable. When I asked him about it on Twitter, he said: “UBI can’t be funded until we have integrity in tax base. Our work on a modest UBI & funding says fix the hole first.”

But the capital income tax doesn’t “fix the hole” in New Zealand’s tax system, because the policy explicitly says that any money it raises will be offset by income tax cuts.

Morgan also said: “Financing that [the UBI] is a real challenge. There’s a way but it would be a step too far at this time.” I’m not sure what that “way” is. But at any rate, the UBI won’t be part of “phase 1” of TOP, however long that lasts.

I think this is significant because it contradicts Morgan’s two claims on launching TOP: that it would radically shake up a middle-of-the-road political establishment, and that it would be evidence-based.

The UBI is one of Morgan’s signature policies, and one of his most radical. (I have reservations about it, but that’s beside the point here.) To drop it, or least put it in the deep freezer, because it would be “a step too far” is exactly the kind of realpolitik-style, unadventurous incrementalism that he has attacked in the existing parties.

The UBI is also, for Morgan at least, evidence-based: he has spent a lot of time arguing that the evidence shows how well it would work. Again, putting it off seems difficult to justify, given his stated aims.

Morgan would, with some justification, probably argue that the capital income tax is quite radical enough already, for the average New Zealander at least. But I’m not sure you can have it both ways, that you can claim that you are going to “light a fuse” under parliament, then back away from one of your signature radical steps because you’re not sure it’s politically achievable.

As a final note, part of the reason the UBI is currently out of bounds for Morgan is that he seems determined to maintain New Zealand’s tax take at its current level, albeit switching some wealth and income taxes. But it’s hard to see why he takes that stance. New Zealand has one of the lowest tax takes in the world, and there’s a very strong (and evidence-based!) argument that we need a bigger tax take to bolster struggling public services (such as health, which has had inflation-adjusted funding cuts of $1.7 billion in the last few years) and improve our economic and social infrastructure.

Sticking to the current tax take isn’t a radical or evidence-based position: it’s a cautious, centrist one. And unless you think that opportunities can be generated for free, or there is currently massive waste in New Zealand public spending, I’m not sure where Morgan will find the money to pay for the other opportunity-generating policies he is presumably going to launch.

So, in short, while I support quite a lot of the policies that Morgan advocates, I’m not sure that his party is going to be able to achieve what he wants it to.

Are the youth of today disenchanted with democracy?

Young people want to see change and are pursuing it outside of conventional parliamentary politics. But parliamentary politics is where power ultimately resides.

Stuff reported last week that young New Zealanders were “losing faith in democracy”, based on a journal article showing that only 29.3 percent of Kiwis born in the 1980s say it is “essential” to live in a democracy.

The story adds:

This is a dramatic drop off from those in older cohorts – almost half of those born in the 1970s believe it is essential, while almost two thirds of those born in the 1930s say as much.

Now, I’m not sure we should take this at face value. It’s not as if large numbers of young New Zealanders show a desire to live in a dictatorship, or with a “strongman” leader in charge (unless I’ve been missing some quite major shifts). I suspect the fact they don’t think it is “essential” reflects not a strong desire for totalitarianism but instead a gradual degradation and diminution of a sense that traditional politics is how you achieve change.

We already know that young people are disengaging with traditional forms of democracy, especially voting. I suspect this is partly because politics seems simultaneously uninspiring – the narrowing of debate and quasi-consensus around middle of the road policies in the last 30 years must increase the sense that voting changes little – and also out of date, in the sense that standard, once-every-three-years political voting hardly offers the responsiveness and transparency that the internet generation gets elsewhere in its life.

For those on lower incomes, inequality must be part of the story too, in the sense that those who feel economically excluded from society are more likely to feel powerless and less likely to be engaged.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that young people are apathetic. They want to see change, and they are pursuing it outside of conventional parliamentary politics, in NGOs and social enterprises. But parliamentary politics does matter – it is where power ultimately resides, and decisions are made – and in that sense, this survey is another reason to think harder about how to reform politics, and reconnect people with it.

If we fail in that task, I don’t think that authoritarianism will be the result; it’s just that we’ll continue to see power shift towards those who do vote (the well off and elderly), and we’ll become an increasingly unrepresentative democracy. Which would also be pretty bad.

The New Zealand Initiative on local government and democracy

More responsibility and freedom for local councils, but some recommendations need further examination.

The New Zealand Initiative think tank yesterday launched The Local Manifesto, calling for more responsibility to be devolved to – and greater freedom for – local councils.

It’s a call I broadly agree with, especially since the think tank points out that local councils are currently too much beholden to central government and not answerable enough to their citizens.

I welcome the recommendation for councils to use more citizen juries, as the city of Melbourne did to get community support for a $5 billion infrastructure plan. (Instead of raising local taxes, the jury recommended lifting developer contributions, selling non-core assets, and increased borrowing.)

Ditto the use of non-binding referenda. They can be problematic, presenting citizens with an overly simplistic choice and, as Christchurch Mayor Lianne Dalziel argued at the report launch last night, overly influenced by “paid advertising”. But the report points out that Whanganui did them well between 2005-10, giving citizens the chance to say which level of rates they preferred (not just a binary choice) and getting significant community engagement.

At the launch, Dalziel also backed participatory budgeting, a process in which citizens directly determine council spending, saying, “Participatory budgeting is one component of what we intend to implement in Christchurch.” I couldn’t find any mention of participatory budgeting in the report itself, but I certainly think it should be on the agenda. It gives people control over meaningful decisions, and forces them to make important trade-offs – more spending on roads means less for parks, and so on – much more than referenda do.

I wasn’t so sure about some of the other recommendations, however. The initiative thinks local councils should be able to opt out of national standards, for instance on water quality, if they think the cost too great. But if a national standard is the absolute minimum, and is backed up by evidence, that doesn’t make much sense. No local area should be able to say, “We know, based on the evidence, that lowering the water below this quality leads to more people falling ill, but we are going to do it anyway.” Arguably what we need instead is more performance-based regulation: central government setting a standard that must be reached, but letting councils decide how to do that.

The report’s advocacy of democracy is slightly undermined by its (admittedly lukewarm) enthusiasm for council-controlled organisations, which may have their advantages but are definitely removing important decisions from citizens’ control.

Finally, the report doesn’t fully grapple with the crucial issue of co-governance with iwi. If iwi are to have what is guaranteed to them under the Treaty of Waitangi – control over key resources – we are going to have to have a massive ramping up of co-governance. That surely is a core part of any genuinely democratic devolution of power – so while I welcome much of the thinking behind this report, some of the implications of its broad thrust remain unexamined.

Labour’s Ready to Work plan: good idea, not sure about the details

Long-term unemployed people will be offered six months’ work on environmental and community projects. But is it compulsory?

At their party conference yesterday, Labour announced a plan, labelled Ready to Work, to give long-term unemployed young people the chance of six months’ work on environmental and community projects.

It’s a good idea, in essence. This kind of work offer helps keep people out of the despondency that unemployment can engender, and helps them acquire work skills and routines. Evaluations of a similar UK scheme, the Future Jobs Fund, were very positive, estimating that it generated a net benefit of several thousand pounds per participant, partly through avoiding long-term downward spirals of worklessness, poor health, low self-esteem, etc.

National’s attacks on the policy haven’t made much sense. Steven Joyce claims it will compete with businesses, but in fact it’s explicitly aimed at the government and NGO sectors. So the policy seems broadly fine.

The problem, as ever, is in the details. Six months is probably the right length of time, and the policy targets young people – one of the specific groups that such policies work well for – who have been unemployed for six months or so, which again is about right.

However, one minor problem is that the jobs appear to be fulltime in that six month period, which won’t leave participants time to look for the other jobs they will need once their time is up. Better designed schemes offer only part-time (20 or 30 hour) jobs to avoid that problem.

A bigger issue is that the jobs planned seem to be all in environmental areas (though there’s some vague mention of “community” projects), whereas successful overseas schemes have asked local councils and NGOs to put up bids to take participants into jobs across all the different policy areas.

This creates more competition between providers, raising the chance of the jobs being meaningful not make-work, and increases the odds of a participant finding a job in an area they are interested in.

This matters because, although Labour has been vague on this, it seems as if the scheme will be compulsory, in effect:

Asked if it would be compulsory for those young unemployed to take up job offers under the scheme, [Andrew] Little said the plan was to do everything possible to encourage them into work, including getting mentors to get them out of bed in the morning if necessary. There were sanctions already in place for those who refused work, and they would apply.

I think this is a bad idea, because that’s working for the dole, effectively, a policy widely avoided by governments of different stripes – and which has been disastrous where it was implemented, by David Cameron’s UK government. And the chance of people enjoying such jobs – and getting something useful out of them – are much reduced if they are enforced.

These concerns, however, could all be fixed in implementation, or between now and the election. In general this seems like a sound – and evidence-based – policy.