The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

The sad end to my near five-year OIA battle with Corrections

We should be concerned about the obvious lack of resources for a crucially important public office.

I am not a New Zealand record holder in many areas of life, but I now believe I hold one title, at least as far as the public record goes: the instigator of the longest, most drawn-out complaint to the Ombudsman about government’s abuse of the Official Information Act.

A few weeks ago, I received a final opinion on a complaint that I lodged in September 2011. Nearly five years elapsed between instigation and completion. Whatever else has happened in this ludicrous affair, one thing is obvious: no result that takes five years can ever be satisfactory. The Ombudsman’s office is colossally under-funded and cannot deal with complaints at anything approaching an appropriate speed.

As to the substance of the complaint, it concerned the Department of Corrections’ decision to use a public-private partnership (PPP) to build the new prison at Wiri. Under a PPP, a private company designs, builds and operates a public facility for several decades.

There are many reasons to object to this method of providing new prisons.* One is that the final cost of the facility has often become greatly inflated, through the negotiation process, from the original cost of building it the normal way when government just tenders the construction part. This puts a big question mark over claims that PPPs provide value for money. I know this because I often wrote about them when I worked as a journalist in the UK.

Accordingly I asked in mid-2011, under the OIA, for Corrections to release to me the initial ‘business case’ for building the prison the normal way. They refused; I complained to the Ombudsman.

I won’t go into all the ins and outs of the next five years, except to say that the usual pattern was that I would hear nothing for months, presumably because the Ombudsman was so over-worked; they would apologise and ask Corrections to release more information; the department would do so, but it would not go any further to answering my request; I would point this out to the Ombudsman; and then the cycle would repeat.

In the end, the Ombudsman forced Corrections to release a lot more information, but found in their favour on the key point, that they were right to refuse to say how much the prison would have cost as a straightforward building contract.

Corrections’ defence was that releasing that information would “prejudice or disadvantage the Department in future procurement negotiations in relation to upgrading existing prisons or building new capacity.” This is because, in future negotiations, “there was a real possibility that a tenderer, with knowledge of the component parts of the Departments’ estimates of costs … would pitch its tendered costings close to the Department’s.”

I think this is quite wrong, and hugely dangerous to the public interest. Surely the point about competition is that if any firm pitches its costs high in order to extract more profit, it will be undercut by another. If that doesn’t happen, there’s no genuine competition, only cartel-like behaviour, and other procurement methods have to be used. More importantly, the public’s right to know whether money is being wasted should trump all these concerns.

All this information is made available in other countries, like the UK, so it’s clearly not necessary to keep it private. The Ombudsman noted that I didn’t provide evidence that this is what happens in the UK, but – amazingly enough – after five years of this, and at a time when I have other projects occupying my energies, I wasn’t going to try to find reports based on files I no longer have and articles behind the paywall of a magazine for which I no longer work.

In any case, that’s the sort of work the Ombudsman’s office should be doing, if it were properly funded. And that fact – the lack of resources for a crucially important public office – is what really stands out from this sorry affair.

*Other reasons to be concerned about PPPs are as follows. Private companies pay more to borrow and have to make profits, so inherently have higher costs than the government does. Drawing up the contracts for such a complex deal costs a fortune – the procurement costs on Wiri alone were $21 million, a feast for the lawyers and other consultants. Even then not all eventualities can be predicted. But once the prison is up and running, the existence of a contract makes it very difficult, or expensive, for the government to change how it wants to run the facility. In the UK, for instance, PPP schools have closed owing to falling rolls but the government has had to keep paying for them, because that’s what the contract stipulated.

New pre-tax income stats out

Our inequality may not be as bad as America’s, but we can’t ignore the cumulative impact of large income and wealth imbalances.

Data on pre-tax incomes for New Zealand in 2013 have just been uploaded to the World Wealth and Income Database. So what do they show?

In 2013, the richest 10% got about 30% of pre-tax income, and within that the richest 1% got 7.7%. In both cases that’s about the same as in 2008, or indeed 2000. That’s in line with other things I’ve written about recently. You have to go back to the mid-80s, when the richest tenth got around 25% and the 1% got 4.9%, to see when the increase occurred.

Of course, these figures – crucially – leave out capital gains, which to my mind are income and which probably go disproportionately to the rich (as they do in other countries). And pre-tax income doesn’t directly tell you about living standards, since post-tax incomes, after taxes and benefits are taken into account, are what really matter. New Zealand’s (developed) world record increase in inequality, mid-80s to mid-2000s, was in large measure spurred by cuts to taxes and benefits.

So you don’t want to make too many generalisations from these figures. But they certainly don’t show that the rich are grabbing an ever-larger slice of the pie, for pre-tax income at least. For the real verdict, on post-tax incomes, we’ll have to wait for the next Household Incomes Report.

The data also bear out the point sometimes made by the NZ Initiative’s Eric Crampton, that our inequality is nothing like as bad as America’s. There, the richest tenth get nearly half of all income, and their 1% get 18%.

I don’t think that in any way makes our problems less real, or that it allows us to ignore the cumulative impacts of at least twenty years of large income and wealth imbalances. But it does show that things could be worse.

Technical note: the data on the WWID are essentially the same ones I’ve written about in other posts, but the WWID team makes adjustments to them to standardise across countries, etc, so their appearance there constitutes a ‘new’ publication of data in the long-term series going back to 1921 and across many nations.

The day I played cricket with Nigel Farage

Farage himself didn’t play much part in the cricket match, but he did turn up wearing, all of things, a pith helmet.

The news last night that Nigel Farage had resigned as leader of UKIP, having helped lead Britain out of the European Union, made me cast my mind back to the time we were briefly united through that most British of mediums, cricket, and he made a rather unpleasant impression on me.

About a decade ago, I was living in London and playing for a social team made up largely of journalists. One summer we went on a weekend tour to Yorkshire, the key fixture of which was a game in a village called Thixendale. It was a picture-postcard sort of place, nestled in amongst the dales, tiny, with a few streets, a pub and a very beautiful cricket ground, fringed with trees. It was, unusually for the UK, a hot summer, and I remember everything there as painted in the colours of green and gold, especially the bare, hazy hills.

The Thixendale cricket team was organised, as I recall, by Farage and his fellow UKIP member of the European Parliament, Godfrey Bloom. Bloom was a Yorkshire gent of the good old-fashioned sexist type, and had recently made headlines by somehow getting himself onto the women’s rights committee of the European Parliament and promptly declaring that one of the key issues for women was that they didn’t “clean behind the fridge enough”.

Farage himself didn’t play much part in the cricket match, but he did turn up wearing, all of things, a pith helmet. For those who don’t know, pith helmets are the solid white hats once worn by British explorers and colonialists in hot climates. It was an extraordinary sight, as if Farage had stepped right out of the last days of the British Raj in India. At any rate he soon went to sleep underneath said helmet.

His son, however, was playing for his team as a bowler, wearing a shirt with the crest of Dulwich College, the elite high school he attended. Farage senior had himself been a pupil there in the 80s, where, according to recent reports, he displayed at an early age “racist and neo-fascist views” and sang Hitler Youth songs.

Bloom, meanwhile, distinguished himself by shouting condescending remarks from the sidelines. His team had a woman playing for them who had previously been a British hockey representative, I think, and as she dispatched one of my deliveries to the cover fence I recall Bloom shouting out, “Good shot … for a girlie.”

Did I, at the time, have any inkling that Farage in particular would one day help lead Britain out of Europe and into its current state of leaderless chaos? Of course not. But some of the key themes of his campaign could have been deduced from that day, in particular the nostalgia for the age when Britain really was ‘great’ – which is to say white, male-dominated, colonialist, and secure in its imperial place in the world.

As many people have already pointed out, much of the Brexit vote came from people who’ve been left behind by globalisation. It’s no surprise that they’re angry; I would be too if the industries in my area had been destroyed and there appeared to be no plan for how my region or class would ever recover, beyond some investment in training and a vague exhortation to work harder so as to compete with the millions of skilled workers coming out of India and China.

The European Union isn’t to blame for any of that, but when people are, quite reasonably, very angry, they’ll look for easy targets; and so they were open to Farage’s seductive, comforting message that everything would be right again if Britain ‘took back control’ – that the country could somehow wind back time and keep out all those nasty foreigners.

I have no idea what’s going to happen next, or where the UK will end up. But it does need to find a better vision for controlling the forces of globalisation, including some new thinking about the role of government in shaping the economy. Otherwise it will continue to fall prey to people like Farage, whose only vision is a basically backwards-looking one, a picture of Britain as it perhaps once was but never should have been, and cannot be again.

The Bare Minimum Budget

This Budget may address some of the consequences of social problems, but it does little to tackle their causes.

The best label for this year’s announcement by Bill English might be the ‘Bare Minimum Budget’. It does the bare minimum to defuse potential political damage in a range of areas – homelessness and health are prime among them – but almost nothing to address the country’s most deep-rooted, systemic social problems. Indeed the Budget hints that these problems may get worse.

There is, in the Finance Minister’s speech, the summary of new initiatives, and the accompanying press releases, no mention that I can see of either poverty or inequality. The government clearly thinks it has dealt with the issue through last year’s $25-a-week increase to beneficiary families, even though that will have only a marginal impact on the issue, since most people in poverty are $100-200 a week short of what they need.

The focus on growth – mentioned ten times in the Finance Minister’s speech – but not on inequality (which is not mentioned once) shows that the government essentially holds to the ‘trickle-down’ line from the 1980s, which is that you don’t need policies for distribution: all you need to do is generate growth and assume that it will somehow end up in the hands of people in poverty. Sadly experience tells us that’s not how it works.

The government would object that the average wage is set to rise to $63,000 a year by 2020, a large jump on its 2008 figure. And that’s to be welcomed, although the median wage will be lower than an average pulled up by CEO salaries.

But figures for labour costs – a slightly technical area of measurement – show that the share of company profits that goes to wage and salary workers is set to decline in coming years. More of their share will be taken by the owners of capital: company owners, investors, banks and shareholders. Since those people are disproportionately well-off already, this is a recipe for growing inequality, and more people missing out on what they need for a decent life.

The government would also object that it’s announced a host of social measures, among which are:

$100m in capital funding for more housing in Auckland

$200m for more social housing in Auckland

$4.2m for low- and no-interest loans to low-income families

$111.5m to support people into employment, including $61m for the Youth Service to help 18- and 19-year-olds at risk of long term benefit use, $26m for targeted case management for 120,000 people on benefits, and $15m for a trial of programmes to improve the employment prospects of prisoners

$20m to help offenders reintegrate

$18m for the Warm Up insulation scheme aimed at 20,000 low-income tenants, and $18m for the Healthy Homes Initiative

$96m for legal aid

$200m for a new vulnerable children service

$50m to reduce barriers to employment especially for people with complex health who would otherwise be on benefits

$43m for children most at-risk of not achieving – 150,000 children with significant time spent in a benefit-dependent family

$50m for better data and evaluation

All of these are welcome, especially the help for offenders. But most only begin to scratch the surface of what’s needed. $200m will get you just another 750 social houses, when there are thousands on waiting lists and 34,000 people homeless in one form or another. $43m for 150,000 at-risk children amounts to $1.80 per child per week, according to PPTA calculations – and there’s no increase in general school budgets, meaning extra costs will be passed onto parents.

The health sector gets another $500m or so a year – but needs $700m a year just to keep up with inflation, according to the CTU’s analysis.

And most fundamentally, this Budget does nothing to tackle poverty and the scandal of over 200,000 children going without the things they need for a decent start in life. Not only is tackling that poverty important in itself, it would have major spillover effects: research shows that boosting family income by $1,000 improves kids’ school marks just as much as $1,000 spent on schools, since parents use the money to help their kids learn.

Instead of fully addressing these poverty-related needs, the government has decided to pay down debt early and float the prospect of tax cuts. The result is a budget that does the bare minimum for political survival, and deals with some of the consequences of social problems – but does little to address the causes of these things.

Revealed: No change in the rich’s income share under National

However, that share is still very large, indicating significant income imbalances.

New data from the IRD show that the share of taxable income going to the richest New Zealanders has not changed under National. However, that share is still very large, indicating significant income imbalances.

The IRD data show that the richest tenth of taxpayers got one-third of all taxable income in both 2008 and 2014. Within that, the richest 1%, about 34,000 people, got over 8% of taxable income.

In contrast, the poorest tenth got just 0.4%.

The income shares are broadly the same in 2014 as they were in 2008. This would suggest that pre-tax inequality has not increased under National. However, the following must be taken into account:

Taxes and welfare payments make a big difference to final levels of post-tax or disposable income inequality, which is the most important measure, and that appears to be rising under National; and

these figures exclude capital gains, which are not reported to the IRD because they are not taxed, and so the figures – in all likelihood – dramatically underestimate the amounts and shares of income going to the richest New Zealanders.

The graph below has more detail. The poorest tenth is decile 1 and the richest decile 10. The 1% are labelled as such.

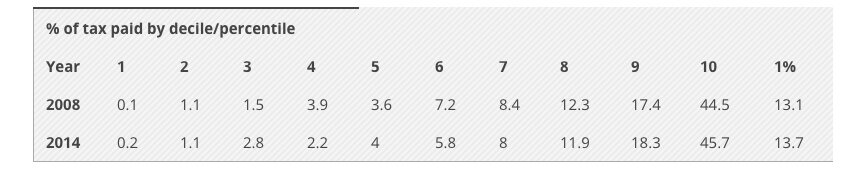

Tax paid

The table below shows the share of income tax paid by the different deciles. It shows those shares have been stable 2008-14. The shares of tax paid by the richest 10% and 1% are large, as would be expected in a system in which they earn a disproportionately large share of income and taxes are modestly progressive (increasing with income). (The apparent change in shares for deciles 3-6 are largely an artefact of the calculation method and probably not significant.)

However, it is important to note that these figures are for income tax only, and do not include GST for instance, so they exaggerate the share of total tax paid by the richest New Zealanders. It is incorrect to say that the richest tenth pay 45% of all taxes.

The stability of tax paid seems surprising, given that the 2010 tax changes cut rates for the richest New Zealanders most dramatically. However, moves to crack down on tax avoidance, such as through loss-attributing qualifying companies, may have had some effect on the richest New Zealanders.

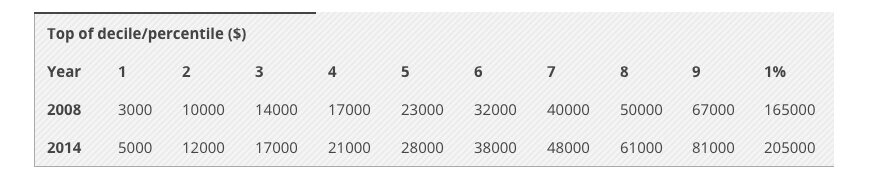

How much does it take to be in the 10%?

The table below shows how much you need to earn, pre-tax, to be in each decile or tenth of taxpayers. The top of decile 5, which is the middle of New Zealand, earns $28,000. To be in the richest tenth you need to have more than the top of decile 9, which is $81,000. To be in the richest 1% you need at least $205,000 a year.

Sources

These figures come from the IRD and can be found at http://www.ird.govt.nz/aboutir/external-stats/revenue-refunds/income-distrib-individual-customers/income-distrib-individ-customers.html.

I thank CTU economist Bill Rosenberg for checking my calculations (and for doing the earlier work that inspired this piece of analysis), although any mistakes remain my responsibility. The 2014 data are provisional at this stage, though any changes are extremely unlikely to alter the high-level figures quoted above.

Revealed: how the government ‘defused’ inequality

Last year’s Budget may have taken a huge amount of heat out of inequality as a political issue, but it may not have changed the long-term pressure.

New data show how the government’s Budget last year took a huge amount of heat out of inequality as a political issue – though it may not have changed the long-term pressure very much.

A previously unpublished poll by UMR shows that the proportion of people listing poverty and inequality as ‘the most important problem facing this country’ fell from 30% just before the 2015 Budget to 20% by late last year – a fall of one third.

This is backed up by figures in the Roy Morgan issues tracker, which displays a similar fall.

This isn’t all the government’s doing: partly what this picks up is people getting more concerned about the state of the world economy, dairy prices and so on, and privileging that over inequality.

But the sharp fall also strongly reflects the way that the 2015 Budget’s key announcement, a $25-a-week increase in benefits for households with children, has convinced a lot of people that the government is ‘doing something’ about the problem.

People who have spoken to ministers say they think they have now ‘defused’ the issue. The move may also explain why, as Brian Easton noted earlier this year, Stuff’s list of political issues to watch out for in 2016 ignored poverty and inequality. With the issue having receded so much by the end of last year, it would have been tempting to write it off.

But UMR’s polling shows concern about poverty and inequality picking up again since late last year and approaching previous heights. As indeed it might. While the $25 increase was welcome, most families in poverty are more like $100-200 a week short of what they need to afford a decent life for them and their children.

Experts such as Prof Jonathan Boston described the 2015 Budget move as having a ‘marginal’ impact on poverty, and this polling suggests the public may ultimately agree. The government’s move has protected them cleverly: it may even be enough to stop voters from deserting them on that issue. But such temporary inoculation doesn’t make the issue go away in the long term. Defusing the issue now is not the same as defusing it for ever.

Is Labour really going to deliver a UBI?

Having a “debate” on something that won’t happen very much runs the risk of looking indecisive.

In news stories this week, senior Labour politicians have suggested they are open to a “debate” on the idea of a universal basic income, a no-strings-attached annual salary paid to everyone in the country.

The basic income has various rationales: increasing human dignity, giving people a base from which to be entrepreneurial, simplifying the benefits system, and, uppermost in Labour’s minds, preparing for a world in which people either change jobs rapidly (and need easy, seamless support between work) or simply can’t find employment because the robots have taken all their jobs.

But is Labour really going to go there? I think not. First, a basic income would be hugely expensive. If you paid each of the 3.5 million adults in this country even a minimal amount, say the $11,000 or so that people like Gareth Morgan have modelled, that would cost $38.5 billion a year, without even thinking about support for children. Paying the basic income at a rate that would keep people out of poverty – that is, at the level of New Zealand Superannuation, around $19,500 a year after tax – would cost $68 billion.

For comparison, we currently spend about $12 billion a year on pensions and $4.3 billion a year on other benefits. So the basic income would be a colossal amount. That’s not to say that it isn’t the right policy, or that there aren’t adjustments, offsets and tax increases you can use to make the cost manageable, but merely that to prepare middle New Zealand for such a policy shift and such spending would take, I think, years of work by a mainstream political party. And Labour has ruled out all the revenue-raising options, like a capital gains tax, that would help fund such a scheme.

Second, you can do much of what Labour is talking about without a basic income. Andrew Little, in one of the stories this week, said: “The question is whether you have an income support system that means every time you stop work you have to go through the palaver of stand-down periods, more bureaucracy, more form filling at the same time as you’re trying to get into your next job.” But if that’s what you want, you could remove stand-down periods, modernise and shift online benefit processes, register everyone in the benefit system when they start work (so that they can move seamlessly from one to another), and so on. You don’t need a basic income.

Finally, another story on this supposed debate claims that the basic income is the same as “the social wage”, and goes on to say: “All Kiwis would be paid a flat income to replace existing social security like pensions and welfare benefits. If a person earns more than the social wage, they won’t get it.”

Now, this is pretty garbled, because the social wage is something quite different; crudely speaking, it’s the dollar value of the free public services people use (which is akin to a wage top-up, hence the term). But the idea that people wouldn’t get the basic income if they earned more than it hints at some kind of claw-back for higher earners.

Assuming that this story represents Labour’s intentions, it suggests that a more likely option is making the benefit system unconditional – that is, you don’t have to be seeking work to get the dole – but not paying the basic income to higher earners. You could argue that that’s a political disaster – since it’s boring, policy-wonk stuff that involves giving some people free money but without the excitement of a full-bore basic income – or smart thinking, since it looks clever and future-focussed without outraging people by giving millionaires ten grand a year.

But either way, it’s not a basic income, nor do I think – from what I hear, and what I feel is politically feasible – that Labour will implement one. I’m happy to be proven wrong, but if not, having a “debate” on something that won’t happen very much runs the risk of looking indecisive, and of raising people’s hopes only to let them down.

Why inequality is such a barrier to eradicating poverty

You may need economic growth to lift people out of poverty, but we need to think about how it will be shared.

In the arguments about how wealth and income are shared out, one of the common lines is that poverty matters, but inequality, in the sense of the gaps across all of society, is a distraction. This is usually buttressed with a reference to China: just look, people say, at the way that hundreds of millions of people have been pulled out of poverty, even as the gap between the rich and the rest has widened. Inequality doesn’t matter; fostering economic growth is the key.

This week’s report from Oxfam – the one pointing out that 62 billionaires have as much wealth as half of the world’s population combined – neatly destroys that argument.

It acknowledges that, between 1990 and 2010, the number of people in the world living below the extreme poverty line halved. But, crucially, it also points out:

Yet had inequality within countries not grown during that period, an extra 200 million people would have escaped poverty. That could have risen to 700 million had poor people benefited more than the rich from economic growth.

The point here is that although countries used some of their economic growth to lift people out of poverty, a disproportionate amount of that growth went to the already rich. Had the growth been fairly shared, poverty would have fallen even more.

The reason that growth wasn’t shared fairly is to do with inequality: the failure to curb monopolies that benefit the wealthy; a lack of bargaining power for workers that sees them unable to claim their share of company profits; weak tax and benefit systems that don’t provide an adequate safety net or recognise the gains everyone gets from public infrastructure; corruption and other ways that wealth influences power. Underlying all that are attitudes about inequality – beliefs that some people are more deserving than others.

So, yes, you may need economic growth to lift people out of poverty; but if you don’t think about how it will be shared, it’s going to be severely limited in its effectiveness. Shared economic growth is a key challenge of the years ahead – and that forces us to think about inequality.

New Zealand not world’s wealthiest country, after all

If something doesn’t seem right, apply your ‘basic common sense’ test, even for well regarded international reports.

A couple of weeks ago, a report from Credit Suisse claimed that New Zealand had the highest median wealth in the world. At the time, I questioned the claim: could the average New Zealander really be wealthier than the average Swede, Australian or Dane? I also thought the figures were well out of line with what my own research was showing.

Turns out I was right to be sceptical. Both the Reserve Bank, whose data the report used, and I got in touch with the report’s authors, and they have confirmed there was an error in the New Zealand figures – due to problems, indeed, with the exchange rate conversion.

The report’s authors have said that the correct figures show the average New Zealander with wealth of around US$252,000, as opposed to the US$401,000 originally quoted. That puts us roughly in the middle of the pack with other Western countries, as one would expect. (And the point remains that those figures are still inflated by our massively over-valued housing market.)

The report’s authors will investigate correcting the online version of the report, and I’ll be contacting the New Zealand newsdesks who have run the story to see if they will do likewise.

The lesson from all this? If something doesn’t seem right, apply your ‘basic common sense’ test, even for well-regarded international reports.

On a related note, for the latest data on this country’s wealth and how unequally it is distributed, you can pick up a copy of my book Wealth and New Zealand from November 9.

Finally, thanks go to the Reserve Bank communications team for following up on this.

Wellington City Council highest earners calculations

WCC has a substantially increased upper salary bill, and the alternative has been open to them to redirect that salary bill increase towards their lowest paid earners.

The Dominion Post is running an opinion piece of mine this morning, comparing the cost of paying the Living Wage to Wellington City Council staff (about $1.7 million a year, on campaigners’ estimates) with the payments for the council’s senior staff in recent years. Below is a spreadsheet with the details of the calculations.

What I have done is take the data from the council’s last four annual reports, which is when they started reporting on the number of staff earning over $100,000. They don’t give exact salary figures for each staff member, in order to protect privacy; instead, they list how many staff members are in the salary bands over $100,000, e.g. $200,000-$280,000.

To come up with the total payments each year to staff who earn over $100,000, I have taken the number of staff in each bracket, assumed they are all earning the midpoint of that bracket, e.g. $240,000 in the example above, and then multiplied the two figures. I have also taken out one of the figures in the top bracket, since that has to be the chief executive and their salary is listed separately. What the figures show is a substantial (30%) increase in both the number of staff earning over $100,000 and the total payments to those staff.

Year Staff on $100k+ Salary bill for $100k+ earners

2011-12 148 $20.4 million

2012-13 155 $21.7 million

2013-14 174 $24.8 million

2014-15 192 $26.8 million

As can be seen, the cost of the Living Wage is about 6.4% of the salary bill for the highest earners, implying that restraint at the top would create ample room for the increases at the lower end.

One question is how much of this increase – about $6.4 million – is an actual increase in pay and how much is just the effect of greater numbers, i.e. people moving up over the line and thus bringing another $100,000 of income into the figures. You can estimate that by taking the increase in staff numbers – 44 – and subtracting the amount they bring into the figures (44 times $100,000 = $4.4 million) from the increase. That leaves about $2 million – still enough to cover the Living Wage costs to the council of around $1.7 million, according to campaigners’ estimates. (Although there will still be pay increases being contributed by those staff, since they are clearly rising in salary, and one could also question the necessity of that number of staff being on or nearly on $100,000.)

Now, it could be that even more of the increase is due to new people coming in (if they were employed in new positions on, say, $250,000). But I’m not aware of that happening at WCC recently; in general, the council has been downsizing, not taking on new staff. And even if that is occurring, it still represents a high pay phenomenon – the employment of larger numbers of highly paid managers – that is a deliberate HR policy. The WCC could take a different policy, that of enabling more staff to be self-managing and flattening management hierarchies, thus eliminating tiers of management and freeing up income to pay lower-paid staff more.

Either way, the point remains that the WCC has a substantially increased upper salary bill, compared with even a few years ago, and the alternative has been open to them to redirect that salary bill increase towards their lowest paid earners. And the costs of increases at the lower end are a very small fraction of the highest earners’ salary bill.