The Good Society is the home of my day-to-day writing about how we can shape a better world together.

A detail from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Renaissance fresco The Allegory of Good and Bad Government

Stuff: How will Hipkins tackle stagnating progress on child poverty?

The prime minister needs to find $1b a year if he is to meet his government’s targets.

Read the original article on Stuff

Prime Minister Chris Hipkins is known to dislike the nickname Chippy, a hangover from his student days.

Given the way he has chewed through Jacinda Ardern’s old policies, maybe we should instead call him the Wood Chipper: big, gnarly policy offcuts are fed in, and out comes a handy pile of pie-related photoshoots and small-target appeals to swing voters.

Judging by Thursday’s poverty statistics, however, Hipkins has a new problem from the past to test his well-honed political skills.

When Labour came to power, it made a big play about addressing child hardship. It was, Ardern made clear, a moral stain on the country, as well as an appalling waste of potential.

Making herself child poverty reduction minister, Ardern set her government immensely demanding targets. Ever since the Rogernomics reforms of the 1980s, and the cruel benefit cuts of the 1991 Mother of All Budgets, New Zealand has had some of the developed world’s worst child poverty rates.

When Ardern came to power, the number of children living below the poverty line – often defined as half the typical household’s income, because that’s the point where paying the bills gets unmanageable – was 16.5%, or one in six.

By 2028, she wanted that down to just 5%, or one in 20. This would represent an extraordinary accomplishment, slashing the amount of misery experienced by struggling families and taking the country from among the developed world’s worst performers to among its best.

In the early years of her government, things went well. The Families Package put $1 billion a year into poor households’ pockets, through the Best Start payment, increases to Working for Families, and other policies.

The poverty rate dropped from 16.5% to around 13% in 2020, lifting 30,000 children above the line and into a better life.

Since then, though, progress has ground to a halt. The child poverty rate, Thursday’s data showed, was about 12% in June last year. On all measures, it was essentially flat between 2021 and 2022.

On the one hand, it is a testament to the government that, during a pandemic, it did not allow overall poverty rates to spike. Some people may ask how the official figures can say as much, given that the media are full of stories of spiralling foodbank use and the catastrophe that is emergency motel housing. But the two stories are not inconsistent.

The most vulnerable people have, during the pandemic, found things unbearably hard; their misery, the depth of their poverty, has clearly increased. But at the same time, tens if not hundreds of thousands of families have benefited from Labour’s ongoing minimum wage increases, tax-credit rises, and a $100-a-week boost to the core benefit since 2018.

That has helped lift, or at least sustain, their incomes, resulting in a flat overall child poverty rate.

Even that, though, poses real problems for Hipkins. Like someone leaving the hardest jobs till last, the Government has pencilled in the biggest poverty reductions for the final period covered by its targets, 2024 to 2028.

Getting the child poverty rate down from its current 12% to the 5% Ardern envisaged would be a mammoth task in just four years. Labour’s problem is that although there are several big levers it can pull to reduce poverty – wages, benefits, housing and services like health and education – it has so far only leaned on them modestly. Its actions, though meaningful, have never matched the image of a great moral mission that was sketched out in Ardern’s rhetoric.

If policies are to match words, we need to lift wages for the 40% of poor children who have a parent in full-time work. We under-invest in retraining and skills schemes for the unemployed. Families on benefits still do not have enough income to lead a life of dignity, and they are denied some Working for Families payments that go to in-work households, even though their children’s needs are just the same.

Some 12,000 places have been added to the social housing stock, but we are still tens of thousands of homes short of where we were in 1991 (adjusted for population). The schools and health clinics servicing poorer families also need greater investment.

In particular, the Government’s own officials have said it needs to deliver a Families Package each term, if it is to meet the targets. But no such package was evident this term.

Hipkins will have to explain how, if re-elected, he will find the required $1b a year. But he seems hamstrung by being, like his predecessors, terrified of talking about tax.

In Labour’s view, better-off New Zealanders don’t like it, and don’t necessarily want to pay more of it to help those who are struggling. The stagnation of progress on child poverty, in other words, reflects Labour’s long-term inability to challenge some of the core assumptions of New Zealand politics.

RNZ: A three-point plan to clean up lobbying and vested interests

Action is needed to preserve the integrity of New Zealand politics.

Read the original article on RNZ

How many times have we been told New Zealand is a country where anyone can get a meeting with a politician? It's a line constantly used to defuse criticism about the influence that lobbyists and vested interests have on big political decisions.

The underlying message has always been false, of course. Constituents have a decent chance of talking to their MP, but access to the real decision-makers - Cabinet ministers - has always been hard to get. Many individuals and NGOs can attest that it is possible to ask repeatedly for a meeting and get nowhere.

Conversely, as shown by Guyon Espiner's devastating reportage this week, some lobbyists have extraordinary connections. They cheerfully send texts inviting ministers and staff to boozy events. And we can be sure the same happened under previous governments. Clearly some people have far more access to ministers than others.

We also know that, unlike many other countries, New Zealand suffers terribly from the 'revolving door' phenomenon, in which people move seamlessly from politics to corporate life and back again. What should be confidential government information gets instantly turned to private use, giving some people an unfair advantage over others and raising the likelihood that public decisions will be perverted to favour private interests.

I am part of a group of experts and academics who have helped Health Coalition Aotearoa, an advocacy group, come up with a three-point plan to clean up lobbying and vested interests.

Point One is a Lobbying Act that would create a register of lobbyists - containing their names and their clients - and an online searchable database of every meeting they have with decision-makers. 'Lobbyist' would be clearly defined, as it is in other countries' regulation, to include only those influencing government as part of their job - not ordinary people contacting their MP.

All lobbying - from NGOs just as much from corporates - would be caught. The aim is not to bar lobbying, as people have a right to contact decision-makers, but to bring it out in the open, so that we can look for imbalances in who is influencing ministers.

The Lobbying Act could also mandate some kind of "cooling-off" period before people leaving politics can start lobbying. Personally, I would suggest a three-year stand-down, so no-one can work in government and lobby in the same Parliament, and so their inside information loses its currency. But I note concerns from Māori researchers that this could create undue problems for people moving between government and iwi or hapū positions, so further work may be needed.

Point Two would be to introduce rules to ensure that contractors, senior public servants, and people appointed to government committees and boards must declare - or even remove - any commercial interest that might bias their decisions. This would apply to, for instance, health advisory board members who represent the alcohol industry, or public servants who own companies that could benefit from their own agency's decisions - a problem RNZ has recently exposed.

Point Three would be to reform the Official Information Act, so that there is proactive publication of advice and research provided to ministers. That way, we can better detect situations where ministers go against that advice, and look more closely to see if vested interests have biased that decision.

Will these ideas be taken up? Because the problem affects all parties, to a greater or lesser extent, few have had incentives to address it. However, the Green Party has long called for action.

What's more, the potential for change is greater now than ever. National might traditionally have resisted action that it saw as being aimed at the business interests that comprise part of its support. But the solutions being offered address all lobbying, not just that carried out by commercial interests, and media reporting has made clear the issue is not limited to the right of politics.

Labour, for its part, might once have been reluctant to take action that could have exposed its own weaknesses, or which could have been (wrongly) attacked for limiting participation in the political process. But it has a clear incentive now to clean up the issue, and will face limited opposition if it does so.

Promisingly, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins has said he "never shut the door on those conversations" about lobbying and cooling-off periods, while National leader Christopher Luxon has said now is "probably a good time to take stock" of the issue.

Reforms of this kind rarely happen without some kind of incident or protracted media coverage to spur action. That spur now appears to be present.

As the election campaign intensifies, my hope is that all parties will be asked to take action on this issue - and that they will see the need to do so. After all, preserving the integrity of political decision-making, and ensuring it serves the public good not private interests, is something in which all parties have a stake.

Stuff: Reviving a modern Ministry of Works necessary to cope with modern infrastructure demands

We need a better way of building infrastructure without costs blowing out.

Read the original article on Stuff

It was, according to some, an outfit of “mere guessers and gamblers”; to others, an organisation “widely respected for its technical expertise”. The Ministry of Works, which from 1870 to 1988 oversaw the roads, railways and power stations that underpinned this country’s prosperity, was always divisive.

Now, in the wake of Cyclone Gabrielle, a proposal to revive it is once more sparking debate. New Zealand’s crumbling public buildings need $210bn of investment, the Infrastructure Commission estimates. Hospitals have sewage leaking down the walls; tens of thousands of state houses are required. To adapt to climate change, post-Gabrielle, the country needs to repair electricity substations and bridges, and build back greener with EV charging points and wind-power plants.

Labour has doubled the previous government’s infrastructure spending. But money alone won’t do it. Our public schemes frequently run late and over budget, suffer quality defects, and cost more than they would overseas. Just look at Transmission Gully.

One response would be to revive the Ministry of Works, which – until it was privatised under David Lange – was an infrastructure titan. Its teams of architects, engineers and other experts scrutinised project plans, designed buildings, oversaw private contractors – and often did the work themselves. Their legacy ranged from the Roxburgh hydro dam to Wellington’s Central Police Station.

All this became terribly unfashionable in the pro-market 1980s, when it was held that government should just “get out of the way” and give the private sector a free hand. But in a thought-provoking 2021 paper, researchers Max Harris and Jacqueline Paul argue for the (re)creation of a Ministry of Green Works. Their call has since been taken up the Council of Trade Unions, and is being heard more loudly in Gabrielle’s wake.

The need for some such agency is, I think, undeniable. The current debate over consultants has revealed how hopelessly, cravenly reliant modern government is on the Deloittes and Chapman Tripps of this world. The state has been hollowed out in recent decades, losing expertise, wisdom and savvy. One of the worst examples came in Kaipara some years back, where, following the grotesque failure of a wastewater project, it became clear the local council was so short-staffed it couldn’t even manage its contracts with private providers – let alone build anything itself.

Central government suffers, too. I spent years as an infrastructure reporter in London, and it became evident to me that British public servants, often trying to procure the one and only large infrastructure deal of their lifetime, were getting done over, time and again, by the sharp-eyed private contractors who did this stuff all day long.

What New Zealand needs, at a minimum, is a ministry of super-procurers: a team of infrastructure experts who have decades of experience behind them and can drive a tough deal with contractors. We should also restore the position of Government Architect and employ more engineers to ensure our public works meet high standards. One of the biggest failures of 1980s market-fundamentalism, after all, is that it ignored imbalances of knowledge. The state must retain some, rather than let it all be dispersed amongst private providers.

Fortunately, Labour knows this. In a little-noticed move late last year, it began repurposing Ōtākaro, the Christchurch rebuild agency, as a super-procurer that will help other departments deliver big projects.

What’s less clear is whether, as Harris and Paul propose, a new Ministry of Green Works should build things itself, employing legions of its own plumbers, electricians and other tradies. The argument is this would save having to pay private profit margins, and help keep a closer eye on quality.

Economic theory suggests, though, that competition and contracting-out works if the state can properly oversee what the private provider does. This is partly why governments outsource stationery, where it’s easy to check quality, but not, in general, prisons, where the evidence suggests it’s very hard to ensure contractors aren’t cutting corners.

The original Ministry of Works never resolved this tension, sometimes buildings things itself and sometimes tendering jobs. Today, the colossal deficiencies of Transmission Gully – the delays, the poor quality road surface, the endless disputes – suggest private contracting can end in debacle. But what, absent competition, would ensure a state construction agency was more efficient?

Sadly, there seems to be little direct evidence of how well the Ministry of Works performed. Rosslyn Noonan’s otherwise excellent history of the organisation, By Design, doesn’t explain how much ministry projects cost per square metre, nor how high their design standards were, compared to equivalent private-sector projects.

So I’d need to see stronger evidence before I embraced the idea of an all-singing, all-dancing Ministry of Green Works. But its advocates are broadly correct. It would be an important move in the ongoing drive to rebuild what is sometimes called state capacity: the government’s ability to provide the public goods on which we all rely.

Spinoff: Saying it’s ‘too late’ to mitigate climate change sounds seductive – but it’s wrong

Adaptation matters, but we can’t give up on mitigation.

Read the original article on the Spinoff

Say what you like about Maureen Pugh, but she’s a fast reader. Having claimed around 10am last Tuesday that she was “waiting” for evidence humans were driving climate change, the National MP was immediately told by her deputy leader, Nicola Willis, that she had “a lot of reading” to do; and just a few hours later, Pugh was reciting a hostage-video-style statement insisting that she did, in fact, accept the scientific consensus on human-made climate change. Since doorstop-sized climate reports from world bodies make for famously hard reading, it was an impressively quick turnaround.

On the other side of this comedy, though, lurks the not-unreasonable suspicion that Pugh doesn’t really believe the words she was made to recite, and nor perhaps do other National MPs. In correspondence posted on Twitter, Port Waikato MP Andrew Bayly said it was “unhelpful” to debate whether climate change was man-made, though under pressure he later acknowledged that “mankind has played a significant part” in warming the planet.

In National’s defence, the party supports the Zero Carbon Act, the corresponding target of no net emissions by 2050, and significant reductions by this decade’s end. Yet despite endorsing the targets, National has opposed nearly every emissions-reducing policy Labour has put forward, while offering little of its own. The 2030 goal cannot be met without difficult political choices. So if its MPs are wavering in any sense, it is not unreasonable to fear that a National government would find itself unable to summon the requisite will, and that the intensity of climate action might slip. It doesn’t help that its likely coalition partner, ACT, would repeal the Zero Carbon Act, and has no substantive climate policy beyond a vague pledge to tie the country’s carbon price to that levied by its main trading partners.

Meanwhile, influential right-wing voices have begun questioning the need for New Zealand to pull its weight. Matthew Hooton used his most recent Herald column to say that since New Zealand’s emissions are so small in the global context, and others aren’t inspired by our stance, we must shift governmental efforts away from cutting emissions (mitigation) and towards managed retreat and flood defences (adaptation). Although domestic emissions might still fall, he wrote, “New Zealand’s era of climate-change mitigation … is over”, while “the era of adaptation has begun”. He added: “Every dollar we now spend on domestic mitigation … is a dollar we cannot invest in adaptation.”

Elsewhere, ACT deputy leader Brooke Van Velden and left-wing commentator Chris Trotter have taken a similar line. It is a seductive message for those who wish to leave their lifestyles undisturbed, and an understandable response to the devastation of Cyclone Gabrielle, an event that concentrates attention on how best to protect vulnerable communities. But it is absolutely the wrong lesson to draw from that disaster.

Firstly, and most obviously, every tonne of carbon that we don’t emit helps reduce global warming and with it the severity of Gabrielle-style storms. Nor can we keep using that tired old excuse that we represent just 0.1% of global emissions. No-one would say that an economic powerhouse like the UK, though representing just 1% of the total, should do nothing; yet if you add up ten small countries like ours, they have the same emissions as the Brits. Clearly each must play its part in getting to net zero: New Zealanders are simply being asked, in the classic phrase, to “do our bit”.

It is also ludicrous to think that, when it comes to climate action, we have somehow got out in front, in a naïve, self-harming attempt to inspire the rest of the world. In point of fact we are dreadful laggards. As UN data shows, we are one of only seven major countries to have increased our carbon emissions since 1990. Ours are up 26%. In Sweden they are down 81%. Emissions have fallen by 49% in the UK, 43% in Germany, and 6% even in the US.

New Zealand’s failure has knock-on effects. Veterans of climate negotiations, such as Oil Change International’s David Tong, argue that developing countries have routinely used the increased emissions of countries like New Zealand as justification for also doing very little. And who can blame them, especially when the developed world’s huge historical emissions are taken into account?

The arguments of climate-action delayers are all the more frustrating given the long history of obfuscation on this issue. The 2014 documentary Hot Air showed how a chorus of right-wing voices – the Business Roundtable, corporate leaders and conservative commentators – used junk science and scare tactics to prevent climate action when it was first needed, back in the 1990s. They drew of course on the tobacco lobby playbook, seeding doubt where there should have been none.

Those now equivocating on man-made climate change, and calling for adaptation not mitigation, may be less cynically motivated than their predecessors. But they are equally mistaken. Climate policy is at yet another crossroads, and some commentators will have no shame in pivoting swiftly from saying “nothing needs to be done” to saying “it’s too late to do anything”. We mustn’t let that message take hold. Adaptation is needed, of course. But we must also reaffirm our commitment to cutting emissions – and keep the pressure on parties like National to prove they really can rise to the task ahead.

Stuff: Forestry slash a perfect emblem of modern capitalism’s failings

But it could also point the way towards a very different kind of economy.

Read the original article on Stuff

Logs everywhere. Logs up the river, where they converge against a bridge and sweep away its foundations; logs down the river, where they roll onto a beach and kill a child paddling in the shallows. Logs in the estuaries, logs on the roads. Logs covering fields in a prickly blanket of branches; logs breaking every fence on the farm; logs as far as the eye can see.*

Such have been the scenes on the East Coast after Cyclone Gabrielle – and after Cyclone Hale, and after the 2018 floods, and after countless such events. Each time, piles of forestry slash – the industry’s discarded logs, branches and offcuts – have been swept off plantations and into other people’s lives, with devastating consequences. And if it isn’t logs, it’s house-high piles of silt washing off the plantations where, once the pines are felled, the bare soil just sits, waiting to be driven into town.

It is, as Tolaga Bay farmer Bridget Parker put it, “total f......g carnage”. She told RNZ slash had destroyed her farm multiple times. “We don't farm logs. Their [forestry companies’] logs and their friggin' silt needs to stay inside their friggin' estate gates."

Even National Party leader Christopher Luxon has lashed the industry, calling it “the only sector I know that gets to internalise the benefit and to socialise the cost”. He’s wrong, of course: farmers have done it for decades. But the latter have at least begun cleaning up their act, and may eventually pay for their carbon pollution. What about forestry’s waterborne pollution, though: how has it so long escaped serious sanction?

Slash, it turns out, is a perfect emblem of modern capitalism’s failings. Many forestry owners are massive overseas conglomerates, insulated from local public pressure. The regulations governing their activities, and the penalties for their misbehaviour, have both been weak.

Meanwhile, their outsourcing of operations to a fragmented mess of non-unionised sub-contractors drives a race to the bottom for wages and working conditions. Forestry is a lucrative industry, having recorded $15bn in underlying profit since 2013, but it shares little of that lucre with its workers, some of whom have earned barely above minimum wage despite decades spent among the pines.

The industry has also had an appalling death rate. It took the late Helen Kelly, as CTU president, to raise the alarm about the fatigued men dying on dark and slippery hillsides, killed ostensibly by falling logs but, more fundamentally, by their employers’ unsafe practices.

All this, though, was out of sight, out of mind for millions of metropolitan New Zealanders. After slash destroyed houses and roads in the 2018 East Coast floods, forestry firms were fined $1.2m, but even that didn’t greatly raise their profile.

Now climate change has swept away their relative anonymity, and with it the social licence to let their offcuts and their silt keep wreaking havoc. They have a problem of sediment, but also sentiment.

An official inquiry, launched this week, may ultimately require firms to strengthen riparian planting or dispose of slash safely. They may also be forced to bear the costs of slash damage, through far higher penalties, good behaviour bonds, or some other mechanism.

Deeper reform may be needed, though. The unpleasant irony is that many pine forests were planted after 1988’s Cyclone Bola to stabilise steep land inappropriate for farming. But clear-felling destroys that stability. Our forestry firms may have to copy their European counterparts, and fell smaller blocks at a time.

Ultimately, some land may not even be suitable for commercial pine, given the inevitable erosion risk between harvest and re-growth, and may be better replanted as permanent native forest. As AUT’s David Hall argues, forestry’s private assets could serve as public infrastructure, delivering climate, anti-flooding and erosion-prevention benefits.

Where pine plantations remain, their slash could – according to last year’s forestry industry transformation plan – be converted into something useful, be it biofuels, bioplastics, or weed-suppressant mats for vineyards. A large bio-refinery, or mobile onsite ‘mini-factories’, could perform the alchemy.

Even if such re-use isn’t yet commercially viable, it might become so, especially with a public subsidy that recognised the collective benefit in reducing pollution and shifting to a circular economy. Meanwhile, a Fair Pay Agreement for forestry would help stop the race to the bottom on wages. A path opens up, away from an extractive industry and towards an inclusive one.

Forestry firms, after all, can change. Following Helen Kelly’s campaigning, deaths have fallen from 10 a year to around three: still too high, but sharply reduced. We now need similar – indeed better – progress on pollution.

As climate change wreaks ever-greater havoc, we’ll have to invest more in our public assets. That means building, or strengthening, the good things, like community centres and telecommunication towers. But it also means protecting the public realm from bad actors.

Stuff: Time to shine a light on waste

The circular economy is a concept we’ll all be hearing more about in future.

Read the original article on Stuff

The Surrealists thought landfills were a society’s subconscious. In dreams, the experiences we have tried to suppress come bubbling up from the depths. In rubbish dumps, society attempts to cast things off and forget the costs of its own pollution; but still, like a nightmare, the garbage rises.

Sometimes landfills explode, strewing trailer-loads of rubbish across pristine coasts and waterways, as happened in 2019 near the Fox River. And the wider problem has begun to press itself onto our conscious mind.

According to the annual Kantar opinion poll, no fewer than three pollution-related issues – plastic build-up, excess waste, and over-packaging – are in the public’s top 10 concerns. We’re slowly acknowledging that we are, quite simply, rubbish at rubbish.

New Zealand generates 781kg of municipal waste per person; only two developed countries have a worse record. Just one-quarter of our waste is recycled or otherwise repurposed. Some 13 million tonnes annually – 760 Interislander ferries filled to the brim – is dumped, a colossal squandering of resources that have been ripped from the earth, used perhaps once or twice, and thrown away.

The results can be seen on beaches littered with coffee-cup lids, plastic bags and bin liners. Rubbish pollutes our shores, leaches into the soil, chokes turtles and dolphins.

And if the end state of these objects is bad, the start is no better: around half the world’s climate-change-inducing emissions are generated in making things, the Ellen Macarthur Foundation estimates. We continuously breach our planet’s boundaries – and the things we consume play a large part in that grim story.

Recycling, the most commonly touted solution, is useful, but won’t by itself save us. Don’t get me wrong: I love recycling. It’s in the blood: my grandmother, Kae Miller, spent part of the 1970s living on the Porirua tip in protest against the lack of recycling. But it’s still a process in which energy and materials are lost.

We need to embrace the wider suite of measures wrapped up in what’s known as the circular economy, a concept set to define the coming decades. It valorises products that are durable and reusable, objects with a life after their initial purpose, items that can circulate multiple times. It is a recipe for simply bringing less stuff into existence.

We can embrace the circular economy as individuals, and in families and communities, by finding sources of pleasure that don’t involve buying things. Where we do have to buy them, and where budgets allow, we can choose better made, more durable objects. (Or renovated ones: I’m typing this column on a refurbished ex-business laptop that runs beautifully.)

We’ve all acclimatised to taking our own shopping bags to the supermarket. In future we’ll carry more such receptacles: Keep Cups for coffee, Tupperware for takeaways. It’s not just things themselves that should be re-used but also their packaging.

We must also, however, act collectively to change the laws and regulations that shape our choices, so that those rules make it easy for us to do the right thing while punishing people who would keep exploiting the planet.

The first step is to place most responsibility where it lies best: with the manufacturers. They need to be made product “stewards”, responsible for an item’s life from conception to disposal.

Too many products are a fused plastic shell, the mechanical parts hidden inside, inaccessible to a would-be repairer. In response, several states have introduced right-to-repair schemes, forcing companies to make easily fixable products, stock spare parts for up to a decade, and stop requiring consumers to get items repaired at expensive, company-linked shops.

People are still unlikely to get their toaster fixed, though, if it’s cheaper to buy a new one. And that points to a wider problem: our economic system doesn’t properly recognise the value in extending products’ lives, nor the damage done by unnecessary waste.

One solution is to change the price of those actions. Some Austrian cities hand out vouchers that give individuals 50% off the cost of fixing goods (up to a few hundred dollars). The Swedes provide tax breaks for repairs.

Such initiatives could be funded by increasing tip fees and levies on manufacturers. We could also reintroduce container deposit schemes – the old “20c for every bottle you return” initiatives that New Zealand once employed and which have slashed plastic-vessel pollution in other countries.

In this new world, polluters would start to bear the social and environmental costs of their actions, while firms would see more financial value in re-using items. Jobs making stuff would be replaced with jobs repairing stuff.

The Ministry for the Environment, which has already proposed several circular-economy initiatives, needs to keep its resolve, and make them reality. For too long, waste has been near-invisible. Bringing it back into the light may prove to be one of the most revolutionary economic changes we could have ever made.

Prospect: Wealth taxes work. Just look at Argentina

Wealth taxes are increasingly popular with the public, and governments now have more tools to enforce them.

Read the original on the Prospect site

Imagine if £450bn of previously hidden assets were suddenly disclosed by Britain’s wealthiest citizens, and became subject to tax. If that seems implausible, it’s simply what has happened in Argentina in recent years.

In 2016, the Argentine government, which has long levied an annual wealth tax on its most prosperous inhabitants, announced an amnesty: if citizens declared hitherto undisclosed wealth, they would be spared prosecution for past unpaid tax. The results were spectacular. Assets worth 21 per cent of Argentina’s GDP, the equivalent of £450bn in Britain, were declared. Revenues from the wealth tax doubled.

The Argentine experience is part of a wider trend that suggests taxing wealth “is definitely more possible today than it was five years ago”, says Juliana Londoño-Vélez of the University of California. Until recently, however, wealth taxes had been on a long, slow decline, their demise hastened by conservatives who successfully painted such levies as an attack on entrepreneurs and a disincentive to saving. Although in the 1990s a dozen European countries levied wealth taxes, that number has since shrunk to three: Norway, Switzerland and Spain. Most developed countries now seek to tax only limited forms of wealth, such as property.

Awareness of growing economic disparities, however, combined with governments’ need for new sources of revenue, has put wealth taxation back on the table. And it is increasingly popular. In September last year, YouGov polling found public support for taxing wealth more, and income less, in every one of the 11 countries surveyed, including the UK, the US, Australia and Canada. And just last week, the same firm’s polling showed three-quarters of Britons back an annual levy of 2 per cent on wealth over £5 million (clear of debts). Under this tax, someone worth £15m would pay £200,000 a year (2 per cent of the £10m they hold over the £5 million threshold).

Some doubt whether the very wealthy, adept at avoiding tax through complex offshore arrangements, could be made to pay such sums. Londoño-Vélez’s research, however, suggests the net is closing, albeit slowly. Argentina’s amnesty was successful in part because countries are increasingly signing treaties which enable them to share bank data on the assets that citizens of one nation hold in the other. In this instance, the US and Swiss tax authorities agreed to start telling their Argentine counterpart what financial assets Argentines held in their banks. The Panama Papers, an explosive leak of tax-haven data in 2016, drastically increased official disclosures from wealthy Argentines who had effectively already been outed.

Governments now have more tools to enforce wealth taxation, Londoño-Vélez says. “It’s an area where there’s a lot of developments happening as we speak.” Tax havens remain “a huge threat”. But, she adds, “I can see where the loopholes are, and I can see how policy can progressively close them.”

The need to tackle economic disparities adds weight to the wealth-tax cause. Wealth is generally twice as concentrated as income (itself very unequally distributed). Recent Oxfam research suggests the world’s billionaires have taken a striking two-thirds of all the new wealth generated since the pandemic. And the world has been more attentive to such questions ever since the publication of Thomas Piketty’s 2014 blockbuster Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which argued that wealth taxation could break up plutocratic concentrations of economic power.

It could also bolster the integrity of the wider tax system. Tracking flows of interest, rent and dividends shows that much income is generated from wealth. And when people are forced to reveal more of the latter, they are also forced to reveal more of the former. Following Colombia’s tax amnesty, the wealthy disclosed over US$12bn of previously hidden assets – but also paid 39 per cent more income tax. A wealth levy, Londoño-Vélez argues, has “a very positive effect on the income tax system”.

Piketty, meanwhile, believes European countries abandoned wealth taxes not because they were inherently flawed, but because the taxes had—under political pressure—become riddled with so many exemptions that they generated little revenue. In certain cases, they also caught the middle classes—something that would be avoided with, say, a tax cutting in at £5 million net worth.

Despite the positive polling, British politicians—especially on the left—may fear the expressed public support is soft, and would melt under the blowtorch of Conservative claims about taxing “wealth creators” and frightening away investment. But Labour could very easily point to Switzerland, which has long had an annual wealth tax that generates roughly 1 per cent of GDP, the equivalent of nearly £21bn a year in Britain.

Such levies have evidently not caused the Swiss state to be suddenly abandoned by its billionaires. Londoño-Vélez, meanwhile, declares herself “optimistic” about the prospects for wealth taxation. “If countries like Colombia and Argentina … have a wealth tax, and have their citizens report their assets,” she says, “I don’t see why it can’t be done in other countries.”

Stuff: On education, we know what Hipkins dislikes better than what he likes

For all the good intentions, little of the reform he has introduced would survive a change in government.

Read the original on Stuff

Policies, promises, compromises: if you want to know what Chris Hipkins might do as this country’s leader, it’s all there in his record as minister of education, the post he held from 2017 until this week.

Sure, he loves DIY, sausage rolls and Cossie Clubs. But to understand the ideas he’d implement, we should examine his achievements, or lack thereof, to date. For his approach to schooling – to take just one part of his legacy – is a microcosm of this Government’s record, where ambition has outstripped actual change.

Of course, some problems that bedevil New Zealand education – like the slow-motion collapse of our global rankings in literacy and numeracy – are long-standing and driven partly by forces of poverty and discrimination that are well beyond Hipkins’ control.

He’s had to battle obstacles ranging from Winston Peters, in his first term, to Covid, in his second. And he’s done repair work. Cathy Wylie, a respected education researcher, points out that under National, the ministry’s curriculum section “was pretty well disbanded”. That hollowing-out of capacity had to be fixed.

Hipkins always knew what he didn’t like. National Standards and charter schools were both swiftly – and rightly – dispatched.

What he does like can be harder to discern. Clarence Beeby, the legendary post-war director of education, once described schooling’s mission thus: “All persons, whatever their ability, rich or poor, whether they live in town or country, have a right as citizens to a free education of the kind for which they are best fitted and to the fullest extent of their powers.” It’s safe to say nothing so clear or inspiring has emerged from the ministry in recent years.

And the two big wins on Hipkins’ watch – the replacement of the flawed decile system with an “equity index” for funding poorer schools, and the new history curriculum – owe much to his predecessors as education minister (Hekia Parata) and prime minister (Jacinda Ardern).

He has, however, been willing to address deep-seated, oft-neglected issues, something Wylie believes made him “a very ambitious minister of education, one of the most ambitious we’ve had, probably”.

The curriculum, the structure of NCEA, vocational education, school property, early learning: all have been put up for grabs. The problem is that, instead of decisive action, this has often produced a morass of reviews that move very slowly, all tangled up in each other like badly cast fishing lines. Consultancy spending has ballooned.

Some planned policies, meanwhile, are actively harmful. Confronting the decline in literacy and numeracy, Hipkins could have focused on the upstream sources of the issue, but is instead piloting compulsory tests that vast numbers of 15-year-olds will flunk, derailing their education.

Other moves have been more positive. Wylie was a member of the 2019 review of Tomorrow’s Schools, which exposed the system’s big flaw: the way that competition isolates schools from each other, leaving struggling establishments to their fate and making it harder for successful strategies to be shared.

The review’s solution – greater co-operation between, and support for, schools – is slowly being adopted. The ministry has been restructured to help it interact better with teachers and schools. A new education service agency, Te Mahau, will assist those who are struggling. Leadership advisers have been appointed to support principals, and the ministry has removed schools’ ability to manipulate their zones and steal others’ (well-off) pupils.

The foundations of reform are being laid. But how many will endure? In my judgment, only a few changes have built enough momentum and popular support not to be overturned if Hipkins loses October’s election.

Transformational moments have come and gone. When Covid struck, the ministry scrambled to get computers into low-income homes, to aid remote learning. But this never developed – as it should have – into a national mission to ensure every home had the devices and the broadband needed to eradicate the digital divide.

A final anecdote is telling. When the Tomorrow’s Schools reviewers got underway, Hipkins asked them to speak to other political parties, including National and ACT, to test their ideas. “He wanted something that was robust and defensible, and likely to get support,” Wylie says.

Though sometimes labelled a “tribal” politician, Hipkins is, ultimately, a pragmatist, she adds. “He does his homework and he asks good questions... He’s unlikely to come out of left field with something that hasn’t been tested or discussed well. He’s not someone who would have random enthusiasms.”

So there you have it. Collective values and solid analysis, but in the service of pragmatism; greater clarity on what is opposed than what is supported; good intentions that get bogged down in reviews; foundations laid but with little guarantee they’ll endure; Covid opportunities passed up: as it is with this Government, so has it been in education.

Don’t expect too much new from prime minister Hipkins, in short. The singer changes but the song remains the same.

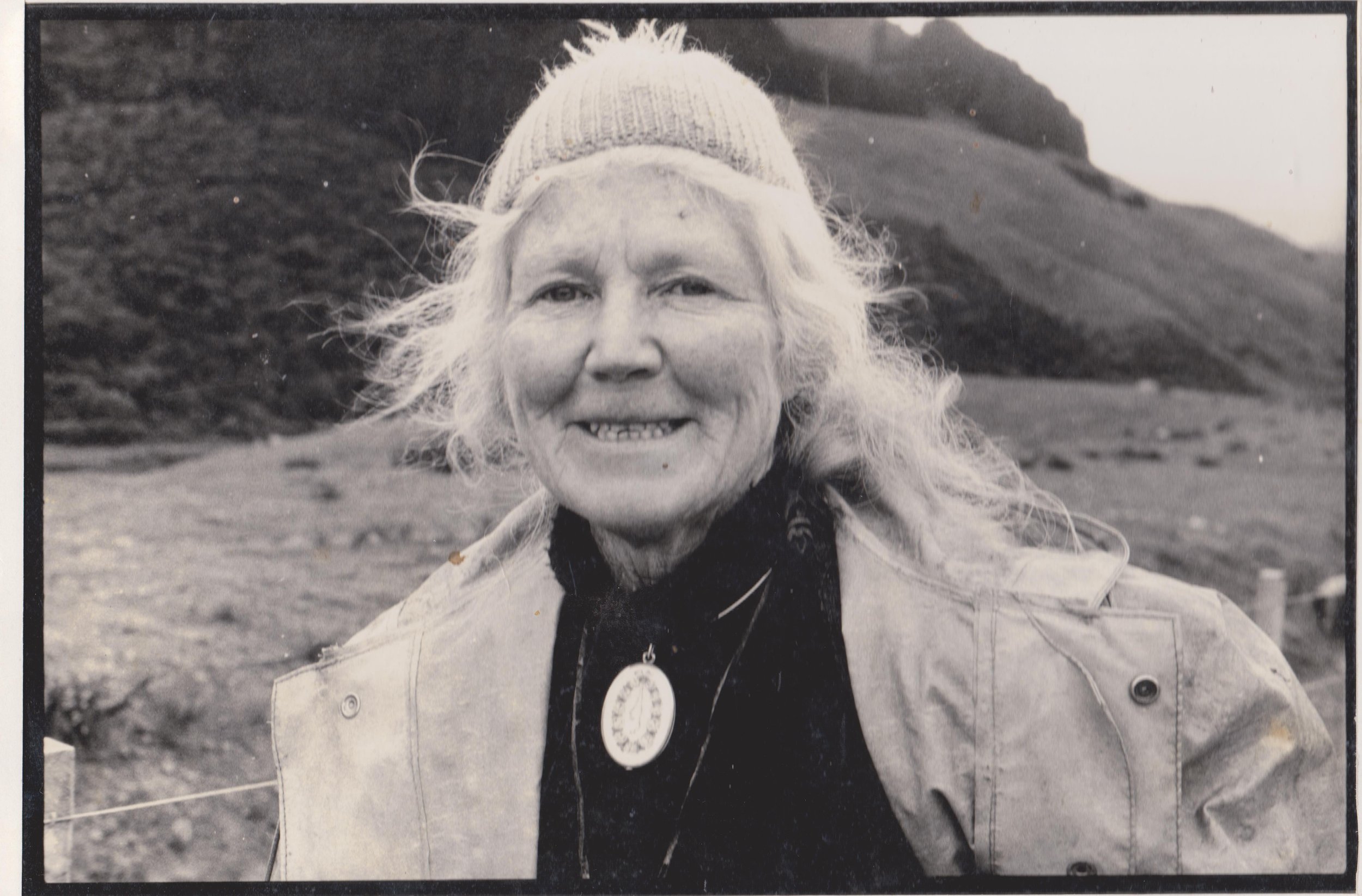

Kae Miller

Two photographs of my grandmother, a pioneering campaigner.

Below are two photographs of my maternal grandmother Kae Miller, a pioneering conservationist, peace advocate and mental health activist. Both photos are released under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

Stuff: Is the electorate in the mood for radical changes?

Incrementalism, radical or not, has ruled the roost. But the electorate might finally want something else.

Read the original on Stuff

“In politics,” the US president John Adams once wrote, “the middle way is none at all.”

But don’t tell that to politicians in New Zealand, where the middle way has been the only path trodden for decades now. Helen Clark, John Key, Bill English and Jacinda Ardern have all eschewed sweeping change.

Not that political life has been preserved in aspic: Clark (and her deputy Michael Cullen) gave us Working for Families, KiwiSaver and the Super Fund; Key part-privatised state energy companies and seeded charter schools; and Ardern’s governments have passed the Zero Carbon Act and raised benefits by $100 a week.

None of this, though, has radically changed this country, or fixed our long-standing deficiencies: elevated levels of poverty and inequality; poor productivity and low investment in R&D; underfunded public services; polluted rivers and lakes; extremely high greenhouse-gas emissions; appallingly expensive, cold and mouldy homes; and a ranking as just about the worst developed country in which to raise a child.

Some commentators blame this on MMP: its coalition governments, they argue, tend to hug the centre and block the radical change New Zealand needs.

But if a radical-change constituency had existed, politicians would have indulged it. I suspect it simply hasn’t been there.

This may reflect the lingering trauma of the 1980s, when finance minister Roger Douglas deliberately and undemocratically acted at breakneck pace, so that opponents had no time to respond.

Clearly the public has been content with political caution. Even after nine years of the last National government, 60% of New Zealanders said the country was on the right track. They weren’t demanding major change.

Labour’s response, at least rhetorically, has been to govern based on what Education Minister Chris Hipkins once told me was “radical incrementalism”: small steps towards a clearly stated and transformative goal.

This he distinguished from both the “crash-through” change of the 1980s and the “muddling-through” of recent governments unwilling to spell out their real goals lest it frighten the horses.

The theory of change – to the extent there was one – held that if people liked a small initial step, they would be “warmed up” to accept a bigger one. Where, though, has this really worked?

Perhaps with benefit increases, which the Government has cunningly made in increments of $20 a week here and there, profoundly changing beneficiaries’ incomes without much controversy. Even here, though, reform has fallen far short of the transformative vision of the 2019 Welfare Expert Advisory Group.

Fair Pay Agreements and social unemployment insurance would, if implemented, be modestly radical – but their fate hinges on the election, and they haven’t obviously been part of an incremental plan.

Elsewhere, the Zero Carbon Act has set the scene for the $4.5 billion Climate Emergency Response Fund, incrementally reshaping environmental politics, but concrete action remains lacking. And although Three Waters represents a gradual ramping-up of co-governance, it has – famously – not been well-received.

I think radical incrementalism has largely been a bust, for two reasons. First, it’s not clear that most ministers had a roadmap to a truly radical destination – or even wanted one.

Second, the theory of change has a clear flaw. Small initial steps don’t always warm people up to accept something bigger: often they can, despite their ostensibly humble ambitions, spark a massive political fracas; and with supporters exhausted, and opponents’ backs up, ministers may become less likely to step up the pace. Incrementalism can burn off, not build, political capital.

And here’s the killer irony: well before Hipkins started talking about radical incrementalism, Bill English was describing his government’s approach as “incremental radicalism”. Same house, slightly different paint colour.

But might incrementalism be junked this year? The above-mentioned right-track indicator fell sharply in 2022, as frustration over Covid and the cost-of-living crisis coalesced. In November a record-high 55% of Kiwis said the country was on the wrong track.

Having abandoned its internationally unusual positivity, New Zealand’s political mood is now closer to that of other developed countries – many of which have been roiled by populist revolts.

Commentator Matthew Hooton says Auckland polling reveals an “incredibly angry” electorate.

Meanwhile, we face what you might call a sidecar election.

On current polling, we’d have an extremely rare result in which the two flanking parties, ACT and the Greens, got around 10% each, while the two majors, Labour and National, got under 40%.

Sidecars like ACT and the Greens don’t have to deal with the nervous median voter. But if they keep polling well, one or the other could win unprecedentedly large concessions from their centrist big sibling.

The right is best placed, of course, to capitalise on the souring of the public mood. But it’s not inconceivable that the left could, too.

Either way, the age of small changes – of radical incrementalism and incremental radicalism – might be coming to a close.